No Markets, Then No Water. California’s Avoidable Crisis

This is what happens in a world without markets for water, as Eli Saslow reports in the Washington Post:

Their two peach trees had turned brittle in the heat, their neighborhood pond had vanished into cracked dirt and now their stainless-steel faucet was spitting out hot air. “That’s it. We’re dry,” Miguel Gamboa said during the second week of July, and so he went off to look for water….

For a few days now, they had been without running water in the fifth year of a California drought that had finally come to them. First it had devastated the orchards where Gamboa and his wife had once picked grapes. Then it drained the rivers where they had fished and the shallow wells in rural migrant communities. All the while, Gamboa and his wife had donated a little of their hourly earnings to relief efforts in the San Joaquin Valley and offered to share their own water supply with friends who had run out, not imagining the worst consequences of a drought could reach them here, down the road from a Starbucks, in a remodeled house surrounded by gurgling birdbaths and towering oaks.

The article reads like science fiction. And it’s so tragic, because markets could go a long way toward allocating California’s water to its highest-valued uses, as Peter Van Doren and Gary Libecap discussed recently. More Cato studies on water markets here.

Posted on July 21, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cronyism in Maryland

Martin O’Malley, the former governor of Maryland and Democratic presidential candidate, is no Bill and Hillary Clinton, who have made more than $100 million from speeches, much of it from companies and governments who just might like to have a friend in the White House or the State Department. But consider these paragraphs deep in a Washington Post story today about O’Malley’s financial disclosure form:

While O’Malley commanded far smaller fees than the former secretary of state – and gave only a handful of speeches – he also seemed to benefit from government and political connections forged during his time in public service.

Among his most lucrative speeches was a $50,000 appearance at a conference in Baltimore sponsored by Center Maryland, an organization whose leaders include a former O’Malley communications director, the finance director of his presidential campaign and the director of a super PAC formed to support O’Malley’s presidential bid.

O’Malley also lists $147,812 for a series of speeches to Environmental Systems Research Institute, a company that makes mapping software that O’Malley heavily employed as governor as part of an initiative to use data and technology to guide policy decisions.

I scratch your back, you scratch mine. That’s the sort of insider dealing that sends voters fleeing to such unlikely candidates as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

These sorts of lucrative “public service” arrangements are nothing new in Maryland (or elsewhere). In The Libertarian Mind I retell the story of how Gov. Parris Glendening and his aides scammed the state pension system and hired one another’s relatives.

In some countries governors still get suitcases full of cash. Speaking fees are much more modern.

Posted on July 17, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The French Revolution and Modern Liberty

Today the French celebrate the 226th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the date usually recognized as the beginning of the French Revolution. What should libertarians (or classical liberals) think of the French Revolution?

The Chinese premier Zhou Enlai is famously (but apparently inaccurately) quoted as saying, “It is too soon to tell.” I like to draw on the wisdom of another mid-20th-century thinker, Henny Youngman, who when asked “How’s your wife?” answered, “Compared to what?” Compared to the American Revolution, the French Revolution is very disappointing to libertarians. Compared to the Russian Revolution, it looks pretty good. And it also looks good, at least in the long view, compared to the ancien regime that preceded it.

Conservatives typically follow Edmund Burke’s critical view in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. They may even quote John Adams: “Helvetius and Rousseau preached to the French nation liberty, till they made them the most mechanical slaves; equality, till they destroyed all equity; humanity, till they became weasels and African panthers; and fraternity, till they cut one another’s throats like Roman gladiators.”

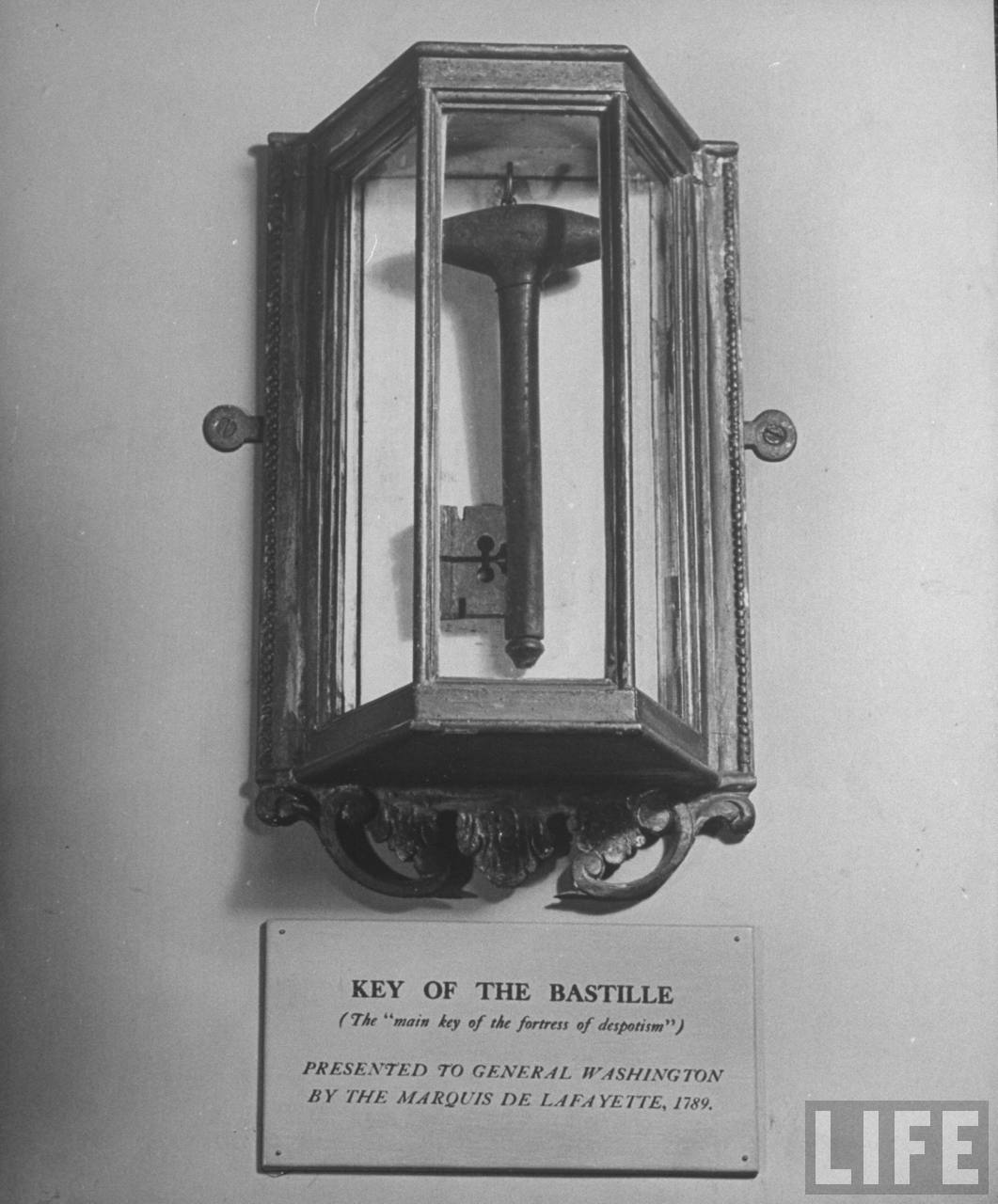

But there’s another view. And visitors to Mount Vernon, the home of George Washington, get a glimpse of it when they see a key hanging in a place of honor. It’s one of the keys to the Bastille, sent to Washington by Lafayette by way of Thomas Paine. They understood, as the great historian A.V. Dicey put it, that “The Bastille was the outward visible sign of lawless power.” And thus keys to the Bastille were symbols of liberation from tyranny.

Traditionalist conservatives sometimes long for “the world we have lost” before liberalism and capitalism upended the natural order of the world. The diplomat Talleyrand said, “Those who haven’t lived in the eighteenth century before the Revolution do not know the sweetness of living.” But not everyone found it so sweet. Lord Acton wrote that for decades before the revolution “the Church was oppressed, the Protestants persecuted or exiled, … the people exhausted by taxes and wars.” The rise of absolutism had centralized power and led to the growth of administrative bureaucracies on top of the feudal land monopolies and restrictive guilds.

The economic causes of the French Revolution are sometimes insufficiently appreciated. In his book The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation, Florin Aftalion outlines some of those causes. The French state engaged in wars throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. To pay for the wars, it employed complex and burdensome taxation, tax farming, borrowing, debt repudiation and forced “disgorgement” from the financiers, and debasement of the currency. Lord Acton wrote that people had been anticipating revolution in France for a century. And revolution came.

Liberals and libertarians admired the fundamental values it represented. Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek both hailed “the ideas of 1789” and contrasted them with “the ideas of 1914” — that is, liberty versus state-directed organization.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man, issued a month after the fall of the Bastille, enunciated libertarian principles similar to those of the Declaration of Independence:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights… .

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression… .

4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights… .

17. [P]roperty is an inviolable and sacred right.

But it also contained some dissonant notes, notably:

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation… .

6. Law is the expression of the general will.

A liberal interpretation of those clauses would stress that sovereignty is now rested in the people (like “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”), not in any individual, family, or class. But those phrases are also subject to illiberal interpretation and indeed can be traced to an illiberal provenance. The liberal Benjamin Constant blamed many of France’s ensuing problems on Jean-Jacques Rousseau, often very wrongly thought to be a liberal: “By transposing into our modern age an extent of social power, of collective sovereignty, which belonged to other centuries, this sublime genius, animated by the purest love of liberty, has nevertheless furnished deadly pretexts for more than one kind of tyranny.” That is, Rousseau and too many other Frenchmen thought that liberty consisted in being part of a self-governing community rather than the individual right to worship, trade, speak, and “come and go as we please.”

The results of that philosophical error—that the state is the embodiment of the “general will,” which is sovereign and thus unconstrained—have often been disastrous, and conservatives point to the Reign of Terror in 1793-94 as the precursor of similar terrors in totalitarian countries from the Soviet Union to Pol Pot’s Cambodia.

In Europe, the results of creating democratic but essentially unconstrained governments have been far different but still disappointing to liberals. As Hayek wrote in The Constitution of Liberty:

The decisive factor which made the efforts of the Revolution toward the enhancement of individual liberty so abortive was that it created the belief that, since at last all power had been placed in the hands of the people, all safeguards against the abuse of this power had become unnecessary.

Governments could become vast, expensive, debt-ridden, intrusive, and burdensome, even though they remained subject to periodic elections and largely respectful of civil and personal liberties. A century after the French Revolution, Herbert Spencer worried that the divine right of kings had been replaced by “the divine right of parliaments.”

Still, as Constant celebrated in 1816, in England, France, and the United States, liberty

is the right to be subjected only to the laws, and to be neither arrested, detained, put to death or maltreated in any way by the arbitrary will of one or more individuals. It is the right of everyone to express their opinion, choose a profession and practice it, to dispose of property, and even to abuse it; to come and go without permission, and without having to account for their motives or undertakings. It is everyone’s right to associate with other individuals, either to discuss their interests, or to profess the religion which they and their associates prefer, or even simply to occupy their days or hours in a way which is most compatible with their inclinations or whims.

Compared to the ancien regime of monarchy, aristocracy, class, monopoly, mercantilism, religious uniformity, and arbitrary power, that’s the triumph of liberalism.

Posted on July 14, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses heroes of freedom on FBN’s Stossel

Posted on July 10, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his book The Libertarian Mind on KCUR’s Up to Date

Posted on July 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses how to talk to progressive family members on an FBN Stossel web exclusive

Posted on July 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

South Carolina Should Move the Confederate Flag

The South Carolina Senate has voted to remove the Confederate battle flag from the grounds of the state capitol. The House still has to vote, and Gov. Nikki Haley has already urged that the flag be moved. The flag was moved from its position atop the capitol dome back in 2000. Now it’s time to move it entirely off the capitol grounds.

In 2001, 64 percent of Mississippi voters chose to keep the Confederate battle cross in their official state flag. At the time I wrote:

It seems that I have every reason to side with the defenders of the flag: I grew up in the South during the centennial of the Civil War—or, as we called it, the War Between the States, or in particularly defiant moments, the War of Northern Aggression. My great-grandfather was a Confederate sympathizer whose movements were limited by the occupying Union army. I’ve campaigned against political correctness and the federal leviathan. I think there’s a good case for secession in the government of a free people. I even wrote a college paper on the ways in which the Confederate Constitution was superior to the U.S. Constitution.

Much as I’d like to join this latest crusade for Southern heritage and defiance of the federal government, though, I keep coming back to one question: What does the flag mean?

I noted that defenders of the 1894 flag and other public displays of Confederate flags

say that the Civil War was about states’ rights, or taxes, or tariffs or the meaning of the Constitution. Indeed, it was about all those things. But at bottom the South seceded, not over some abstract notion of states’ rights, but over the right of the Southern states to practice human slavery. As Gov. James S. Gilmore III of Virginia put it in his proclamation commemorating the Civil War, “Had there been no slavery, there would have been no war.” Mississippi didn’t go to war for lower tariffs or for constitutional theory; it went to war to protect white Mississippians’ right to buy and sell black Mississippians.

We still hear those claims: the Confederate flag stands for history, states’ rights, resistance to an overbearing federal government, Southern pride. For some people it probably does. But those who seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America were pretty clear about what they were seeking.

Historian James Loewen points out:

Yet when each state left the Union, its leaders made clear that they were seceding because they were for slavery and against states’ rights. In its “Declaration of the Causes Which Impel the State of Texas to Secede From the Federal Union,” for example, the secession convention of Texas listed the states that had offended the delegates: “Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa.” Governments there had exercised states’ rights by passing laws that interfered with the federal government’s attempts to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Some no longer let slave owners “transit” across their territory with slaves. “States’ rights” were what Texas was seceding against. Texas also made clear what it was seceding for — white supremacy:

We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.

And thus, as I wrote back in 2001,

The political philosopher Jacob T. Levy [now the author of Rationalism, Pluralism, and Freedom] points out that official state symbols are very different from privately displayed symbols. The First Amendment protects the right of individuals to display Confederate battle flags, Che Guevara posters and vulgar bumper stickers. But official symbols – flags, license plates, national parks – are a different matter. As Levy writes: “When the state speaks … it claims to speak on behalf of all its members…. Democratic states, especially, claim that their words and actions in some sense issue from the people as a whole.”

The current Mississippi flag – three bars of red, white and blue along with the Confederate cross – cannot be thought to represent the values of all the people of the state. Indeed, it doesn’t just misrepresent the values of Mississippi’s one million black citizens; it is actively offensive to many of them. As Levy writes, “Citizens ought not to be insulted or degraded by an agency that professes to represent them and to speak in their name.” Can we doubt that black Mississippians feel insulted and degraded by their state flag?

As long as the violence and cruelty of slavery remain a living memory to millions of Americans, symbols of slavery should not be displayed by American governments.

Note this point, one that many readers seemed to overlook, “The First Amendment protects the right of individuals to display Confederate battle flags.” I still believe that. The First Amendment, of course, also allows private businesses to refuse to sell Confederate flags or even to repaint the car from the TV show “Dukes of Hazzard.” The public-private distinction is crucial here: Private individuals, clubs, and businesses have First Amendment rights. Governments speak in the name of all their citizens.

I urge the government of South Carolina to cease speaking in a way that inevitably offends many thousands of its citizens.

By the way, I know there are some who say, “oh yeah, what about the U.S. flag? It flew over slave states too.” Yes, it did, and that’s a blemish on American history. But it was the flag of “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” however imperfectly it has lived up to those aspirations. Slavery wasn’t just a blemish on the Confederacy, alas. The Confederacy was a new nation, conceived in the defense of slavery, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are not created equal. That’s the difference.

Posted on July 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Imports Are Why We Want More Trade

Sen. Orrin Hatch, R–Utah, author of the recently passed Trade Promotion Authority bill, makes the usual case for trade agreements and TPA:

“We need to get this bill passed. We need to pass it for the American workers who want good, high-paying jobs. We need to pass it for our farmers, ranchers, manufacturers, and entrepreneurs who need access to foreign markets in order to compete.”

Hatch is as confused as most Washingtonians about the actual case for free trade.

This whole “exports and jobs” framework is misguided. In the Cato Journal, economist Ronald Krieger explained the difference between the economist’s and the non-economist’s views of trade. The economist believes that “the purpose of economic activity is to enhance the wellbeing of individual consumers and households.” And that “imports are the benefit for which exports are the cost.” Imports are the things we want—clothing, televisions, cars, software, ideas—and exports are what we have to trade in order to get them.

And thus: “The objective of foreign trade is therefore to get goods on advantageous terms.” That is why we want free—or at least freer—trade: to remove the impediments that prevent people from finding the best ways to satisfy their wants. Free trade allows us to benefit from the division of labor, specialization, comparative advantage, and economies of scale.

“This whole ‘exports and jobs’ framework is misguided.”

Hatch isn’t alone in missing this point. President Barack Obama’s official statement on “Promoting U.S. Jobs by Increasing Trade and Exports” mentions exports more than 40 times; imports, not once. Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, a former U.S. trade representative, says that a trade agreement “is vital to increasing American exports.”

If Saudi Arabia would give us oil for free, or if South Korea would give us televisions for free, Americans would be better off. The people and capital used to produce televisions—or produce things that were traded for televisions—could then shift to producing other goods.

Unfortunately for us, we don’t get those goods from other countries for free.

Sometimes international trade is seen in terms of competition between nations. We should view it, instead, like domestic trade, as a form of cooperation. By trading, people in both countries can prosper. Goods are produced by individuals and businesses, not by nation-states. “South Korea” doesn’t produce televisions; “the United States” doesn’t produce the world’s most popular entertainment. Individuals, organized into partnerships and corporations in each country, produce and exchange.

In any case, today’s economy is so globally integrated that it’s not clear even what a “Japanese” or “Dutch” company is. If Apple Inc. produces iPads in China and sells them in Europe, which “country” is racking up points on the international scoreboard? The immediate winners would seem to be investors and engineers in the United States, workers in China, and consumers in Europe; but of course the broader benefits of international trade will accrue to investors, workers, and consumers in all those areas.

The benefit of international trade to consumers is clear: We can buy goods produced in other countries if we find them better or cheaper. There are other benefits as well. First, it allows the division of labor to work on a broader scale, enabling the people in each country to produce the goods at which they have a comparative advantage. As the economist Ludwig von Mises put it, “The inhabitants of [Switzerland] prefer to manufacture watches instead of growing wheat. Watchmaking is for them the cheapest way to acquire wheat. On the other hand the growing of wheat is the cheapest way for the Canadian farmer to acquire watches.”

Posted on July 3, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Happy Second of July

Americans are preparing for the Fourth of July holiday. I hope we take a few minutes during the long weekend to remember what the Fourth of July is: America’s Independence Day, celebrating our Declaration of Independence, in which we declared ourselves, in Lincoln’s words, “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

The holiday weekend would start today if John Adams had his way. It was on July 2, 1776, that the Continental Congress voted to declare independence from Great Britain. On July 4 Congress approved the final text of the Declaration. As Adams predicted in a letter to his wife Abigail:

The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.

The Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson, is the most eloquent libertarian essay in history, especially its philosophical core:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Jefferson moved smoothly from our natural rights to the right of revolution:

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

The ideas of the Declaration, given legal form in the Constitution, took the United States of America from a small frontier outpost on the edge of the developed world to the richest country in the world in scarcely a century. The country failed in many ways to live up to the vision of the Declaration, notably in the institution of chattel slavery. But over the next two centuries that vision inspired Americans to extend the promises of the Declaration — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — to more and more people. That process continues to the present day, as with the Supreme Court’s ruling for equal marriage freedom just last week.

At the very least this weekend, if you’ve never seen the wonderful film 1776, watch it Saturday at 3:00 p.m. on TCM.

Posted on July 2, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his Politico article “The Grand Old Party’s future shock” on TRN’s The Jerry Doyle Show

Posted on June 29, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty