In Defense of Globalization

We hear a lot of debates these days about globalization. What is globalization? Globalization is simply the process of the free movement of goods, capital, people, and ideas around the world and across borders.

leadGlobalization is a great boon to the world. It means more specialization and division of labor, which are vital components of economic progress. It makes rich countries richer and brings poor countries out of crushing poverty.

Market reforms within countries are important, but becoming part of the global division of labor has been crucial to the rise of middle classes in China, India, Mexico, Chile, and eastern Europe. The proportion of the world population in extreme poverty, i.e. who consume less than $1.90 a day, adjusted for local prices, declined from 36 percent in 1990 to 10 percent in 2015.

That’s the biggest story of the epoch, maybe the greatest achievement in human history. As Max Roser of Our World in Data points out, newspapers could have run the headline NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN EXTREME POVERTY FELL BY 137,000 SINCE YESTERDAY every day for 25 years.

But people don’t know this!

In a recent poll 66 percent of Americans thought world poverty had doubled. A free economy is not a zero‐sum game. Trade and specialization are win‐win. The pie grows for everyone.

And what’s the alternative? Self‐sufficiency? As Leonard Read and Milton Friedman pointed out, no single person on earth can make something as simple as a pencil. You’d need wood from Oregon, graphite from Sri Lanka, wax from Mexico, castor oil from the tropics, and rubber from Indonesia. Not to mention factories to combine those elements into a pencil.

Andy George, host of the Youtube show How to Make Everything, decided to make a chicken sandwich from scratch. It turned out to mean spending six months and $1,500 growing a garden, turning ocean water into salt, making cheese, and killing a chicken all so he could take a bite of a sandwich truly made from scratch.

From both President Trump and President Biden, we hear a lot about “Buy American.” That’s almost as senseless as making a chicken sandwich from scratch. The raw materials, the labor, and the technology necessary to produce the elements of modern life are spread across the globe. It would be vastly more expensive for any country – the United States, India, Nigeria – to refuse to trade with people in other countries to produce goods cheaply and efficiently.

And if it makes sense to “buy American,” why not “buy California”? “Buy Los Angeles”? “Keep our money here in Hollywood!”

As trade specialist Dan Ikenson observed in 2009, most of our modern products should be labeled “Made on Earth,” produced by “a truly global division of labor, [with] opportunities for specialization, collaboration, and exchange on scales once unimaginable.”

In the past generation globalization has brought more people into the world economy, and billions of people are rising out of poverty.

At the same time Enlightenment values of tolerance and human rights are spreading to more parts of the world, with particular emphasis on the rights of women, racial and religious minorities, and gay and lesbian people.

The Internet is giving people more information, more ways to connect, more commercial opportunities, and more choice. Despite what we may be led to think from the flood of information about the world, we are probably living in the most peaceful era in history.

But economic progress inevitably means change. And change can be painful. Think of the transition from 90 percent of American workers working on farms, to about 2 percent today. Now we’re in similar transitions from manufacturing to services and robots.

Some people get hurt in such transitions. They may lose their jobs, or their businesses, or see their own wages not increasing as fast as other people’s, or simply fear that such consequences may happen. And when people perceive a decline in their income or their relative social status, they often want help, and they want to blame someone. That can mean both a demand for government programs and the scapegoating of villains – whether it’s the bankers, the 1 percent, the Jews, the immigrants, the Mexicans, or whoever – just the opposite of the individualist liberalism that gave us the unprecedented progress we have experienced.

We’ve seen a rise of populist and illiberal forces in countries around the world, on both left and right – with threats to liberty, democracy, trade, growth, and even peace. All the bad new ideas – socialism, protectionism, industrial policy — are really bad old ideas. Libertarians and classical liberals have been fighting them off for more than 200 years, and we need to keep doing it.

Posted on September 22, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

In 1932–33 Leading Intellectuals Used ‘Dictatorial’ as a Positive Recommendation

It’s hard not to despair at the state of public policy discussion these days. Every day’s newspaper contains another bad idea from politicians, pundits, and wonks from across the political spectrum, from rent control to corporate subsidies to trillion‐dollar handouts to costly regulations to red vs. blue cultural war games. It could keep an entire institute busy analyzing, criticizing, and warning about looming policy errors. As bad as the current climate is, though, I was reminded this week that we’ve lived through worse policy enthusiasms.

In his recent book Freedom’s Furies: How Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Ayn Rand Found Liberty in an Age of Darkness, Timothy Sandefur describes the intellectual climate that those “founding mothers of libertarianism” faced in the Hoover‐Roosevelt Depression years:

Between 1917 and 1919, agencies such as the War Industries Board and [Herbert] Hoover’s U.S. Food Administration appeared to vindicate Progressive beliefs in government planning. A decade later, many—including Hoover himself—pointed to that precedent, arguing that the Depression was analogous to a world war and should be dealt with in the same way.

That was the basis for the idea that General Electric’s president Gerard Swope proposed in September 1931. He recommended that the federal government create a system of industrial cartels under which all companies of more than 50 employees would be assigned to a trade association vested with authority to dictate the types and amounts of goods and services businesses could provide, and how much they could charge. This would prevent “destructive” competition, by giving companies the power to prohibit their competitors from reducing prices or introducing new or improved products, which would “stabilize” the economy and ensure full employment. “Industry is not primarily for profit but rather for service,” Swope declared. “One cannot loudly call for more stability in business and get it on a purely voluntary basis.” Although hardly the only such proposal—it mimicked the corporatism already being implemented in Italy and Germany—the Swope Plan gained the most attention and would later form the blueprint for the National Industrial Recovery Act. But at the time, Hoover labeled it “fascism” and rejected it as “merely a remaking of Mussolini’s ‘corporate state.’”

Many similar schemes were offered by prominent intellectuals, including historian Charles Beard, who proposed “A Five‐Year Plan for America” on the Soviet model, and New Republic editor George Soule, whose 1932 book A Planned Society proposed political control over the entire economy. These writers, said one of Soule’s colleagues, “were impatient for the coming of the Revolution; they talked of it, dreamed of it.” And they were not alone. That same year, novelist Theodore Dreiser published Tragic America, which he had originally planned to call A New Deal for America. It advocated the overthrow of capitalism and the replacement of the Constitution with a government that would control industry in the style of the Soviet Union, where he thought communism was “functioning admirably.”…

Dreiser probably changed his title because A New Deal had already been taken by economist Stuart Chase, whose book of that name also appeared in 1932. Chase—who considered it “a pity” that “the road” to socialist revolution in America was “temporarily closed”—looked forward to the day when the government would seize all industry and “solv[e] at a single stroke unemployment and inadequate standards of living.” It would do this, he said, by compelling all individuals to “work for the community.” The government should forbid high interest rates, stock market speculation, the manufacturing of “useless” products, the creation of new clothing styles, businesses “rushing blindly to compete,” and other “ways of making money”—and it should do so “by firing squad if necessary.” The 44‐year‐old Chase was inspired by the “new religion” of “Red Revolution,” which he found “dramatic, idealistic, and, in the long run, constructive.” “Why,” he asked, “should the Russians have all the fun of remaking a world?”

A system of industrial cartels under which all companies of more than 50 employees would be assigned to a trade association vested with authority to dictate the types and amounts of goods and services businesses could provide, and how much they could charge. A Five‐Year Plan. Political control over the entire economy. Replacement of the Constitution with a government that would control industry in the style of the Soviet Union. Seize all industry. Compel all individuals to “work for the community.”

As bad as our policy dialogue is in 2023, we don’t hear mainstream commentators calling for five‐year plans and top‐down control of the entire economy. It seems that libertarian and free‐market ideas, along with our experience of overweening government in the United States and especially in other countries, have had some influence.

At the time, though, these ideas were not just wishful thinking by ivory tower academics. Consider some commentary from March 1933, when Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated as president.

In his inaugural address Roosevelt declared, “We must move as a trained and loyal army willing to sacrifice for the good of a common discipline, because without such discipline no progress is made, no leadership becomes effective. We are, I know, ready and willing to submit our lives and property to such discipline.… I assume unhesitatingly the leadership of this great army of our people dedicated to a disciplined attack upon our common problems.” And if Congress didn’t promptly pass his agenda, “I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.…The people of the United States … have asked for discipline and direction under leadership.” And as Sandefur reports, plenty of people who ought to have seen themselves as guardians of constitutional liberty fell in line:

Fearful Americans cannot have been reassured by the February editorial in Barron’s that advocated “a mild species of dictatorship,” or by Walter Lippmann’s advice to the new president that same month—“You have no alternative but to assume dictatorial powers”—or by the New York Times reporter who proclaimed in May that Americans had given Roosevelt “the authority of a dictator” as “a free gift, a sort of unanimous power of attorney.… America today literally asks for orders.” Publisher William Randolph Hearst—who admired Mussolini and Hitler so much that he gave them columns in his newspapers—financed a propaganda film called Gabriel over the White House, which premiered days after the inauguration and depicted the new president being guided by heaven to declare martial law, unilaterally cure the Depression, execute criminals, and end all war. Even the Nazi Party celebrated Roosevelt’s commitment to all‐encompassing power with a story in its newspaper lauding what it called “Roosevelt’s Dictatorial Recovery Measures.”

In some ways the real counterattack on this collectivist, centralist mindset began a decade later with the publication in 1943 of Paterson’s The God of the Machine, Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom, Rand’s The Fountainhead, and in 1944 of F. A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. But as our current challenges illustrate, this intellectual battle is far from over.

Posted on September 21, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz gives the presentation, “Embracing The Enlightenment: Classical Liberal Response to a Growing Illiberalism,” hosted by Freedom Fest Memphis

Posted on September 21, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Time for Pandemic Emergency Spending to End

New exercises of federal spending power are often justified on the basis of some emergency. Both the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations cited high unemployment and poverty in the Depression as justification for new transfer payments, such as farm subsidies and AFDC (“welfare”). When the emergency ended, the programs continued.

As economists would predict, any government payment program will create its own constituency. Program recipients will not willingly give up their source of income just because the emergency has ended. We’re now dealing with the latest example, the possible sunsetting of pandemic relief payments.

In March 2020, as government started to respond to the spread of the novel coronavirus, multi‐trillion‐dollar relief programs were quickly passed into law. Now some of those programs — and their recipients — are facing statutory deadlines. Which makes sense because the programs were justified on the grounds of keeping firms in business and employees supported. But the COVID-19 emergency has now ended, the economy is strong, and unemployment is low.

As usual, journalists are rushing to cover the plight of people who may lose their emergency benefits. A Washington Post article is headlined, “The incredible American retreat on government aid.” Note first that there is no retreat from the level of government transfer payments that existed in 2019. The concern is simply with new emergency programs dating from 2020 or later. The Post uses urgent language to bemoan

the expiration of a wave of federal programs passed in response to the pandemic to make life easier for millions of Americans.

- Millions — possibly tens of millions — are losing Medicaid coverage, the result of the end of a covid‐era program that gave federal aid to states that kept people continuously enrolled rather than carry out regular purges of the rolls.

- Billions in covid‐era federal funding to keep child‐care centers open expire at the end of September, leaving states to scramble in the face of estimates 70,000 facilities could close and 3.2 million children (mostly five years old or younger) could lose their care.

- That would have enormous ripple effects across the economy, forcing some proportion of parents out of their jobs to care for their children.

The article goes on to mourn the expirations of such other emergency programs as expansion of the Women, Infants, and Children food aid, student loan repayment suspensions, eviction moratoriums, and enhanced unemployment benefits.

Now it’s easy to find individuals who have benefited financially from these programs. But emergency payments, like any other government spending, have detrimental effects as well, and those are not considered in the Post article.

Federal spending skyrocketed in 2020 and beyond, and money diverted to federal purposes is money that is not available to private businesses and individuals, money that doesn’t contribute to job creation and economic growth. It did, however, contribute to the highest levels of inflation since the 1970s.

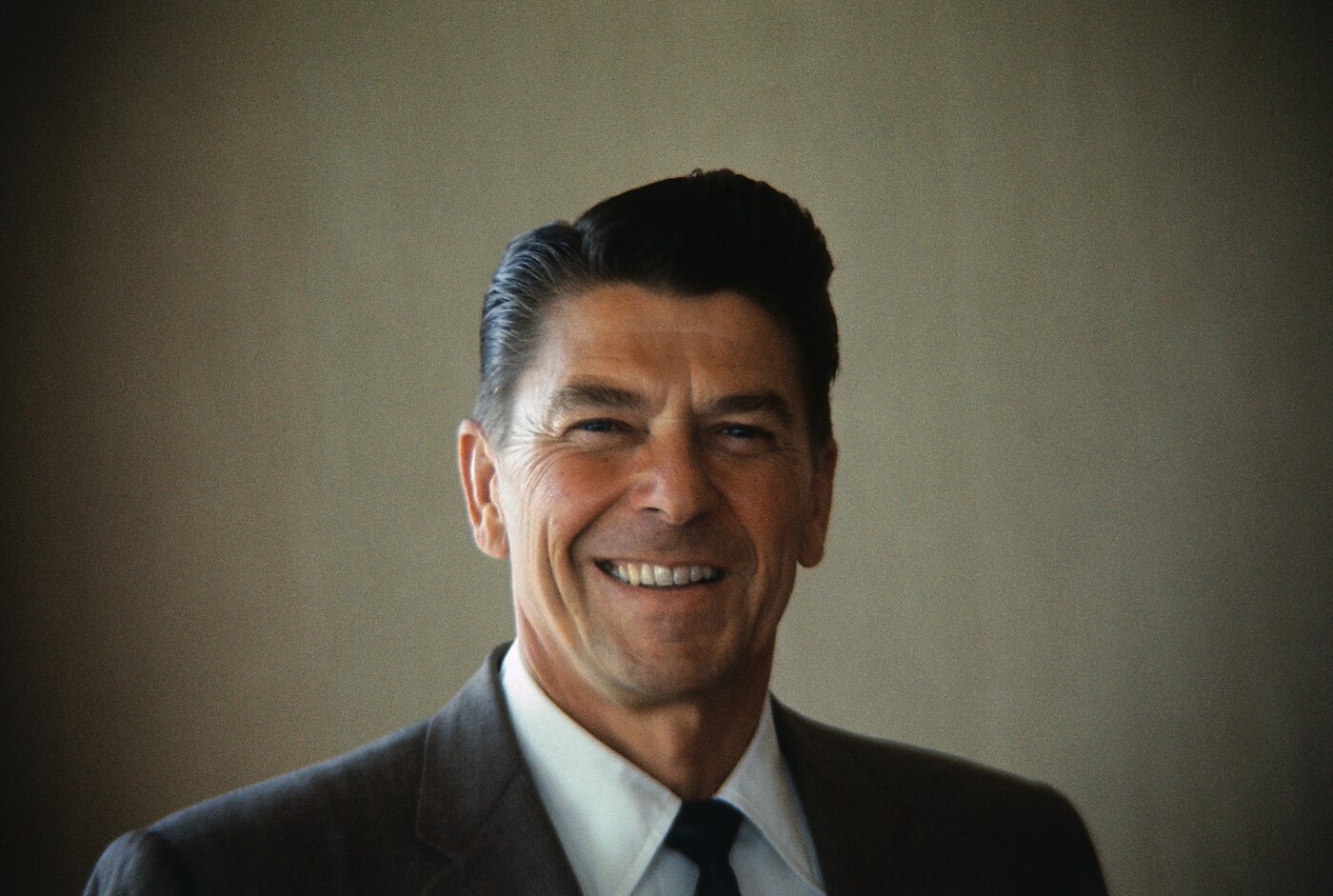

At Cato, we knew the risk that emergency programs would become permanent. As Ronald Reagan said in his famous 1964 speech, “No government ever voluntarily reduces itself in size. So, governments’ programs, once launched, never disappear. Actually, a government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth.”

In March 2020 Cato president Peter Goettler wrote in a letter to lawmakers, “Extraordinary measures must end with the passing of the crisis, and sunset clauses included in all emergency legislation.”

And staff writer Andy Craig wrote, “And perhaps most importantly: emergency rules and powers should extend only for the duration of the emergency, and be repealed at the earliest feasible opportunity. We should be wary of the ratchet effect, where governments tend to retain powers and keep open programs long after their original justification has disappeared.”

But it’s very difficult to get policymakers to make a binding commitment that temporary emergency programs will genuinely end when circumstances change.

That’s why the federal subsidy to wool and mohair producers, created in 1954 to increase domestic production of military uniforms, is still in effect decades after the Pentagon’s interest in the program ended. The difference is, that program is a budgetary rounding error compared to the trillion‐dollar pandemic programs.

In the next perceived crisis, Congress will again move to demonstrate its concern by voting for massive spending programs. I hope that our current experience will remind future legislators to be far more cautious about creating “temporary,” “emergency” spending commitments.

Posted on September 11, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty