Rating the Presidents

Sigh. Another year, another ranking of presidents. And as usual the academics who vote in such surveys especially like presidents who conducted wars and significant expansions of the federal government. Also they like Democrats, more so than in previous years.

This time it’s the Presidential Greatness Project Expert Survey, surveying 154 academic social science experts in presidential politics.

Presidential scholars love presidents who expand the size, scope and power of the federal government. Thus they put the Roosevelts at the top of the list. And for a long time (in a different poll, from Siena College) they rated Woodrow Wilson—the anti‐Madisonian president who gave us the entirely unnecessary World War I, which led to communism, National Socialism, World War II, and the Cold War—6th. Recently he’s fallen to 13th, presumably because of the increased publicity about his racism. In this survey he fell from 10th in 2015 to 15th this year. Not far enough, by a long shot.

Ronald Reagan, who did not resegregate the federal workforce or turn a European war into World War I, fell from 7th in 2018 to 16th this year. President Biden, after three years of vastly expanding the scope and cost of the federal government, is rated 14th. John F. Kennedy, a charismatic guy whose greatest substantive accomplishment was the launch of the Vietnam War, climbed into 10th place. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who never relinquished his claim on power, moved to no. 2, passing George Washington, who twice gave up power, ensuring that the new United States would be a republic. Lincoln is ranked first.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the survey directors write,

this survey has seen a pronounced partisan dynamic emerge, arguably in response to the Trump presidency and the Trumpification of presidential politics.

Proponents of the Biden presidency have strong arguments in their arsenal, but his high placement within the top 15 suggests a powerful anti‐Trump factor at work. So far, Biden’s record does not include the military victories or institutional expansion [!] that have typically driven higher rankings

Self‐described liberal and conservative scholars didn’t diverge much in their rankings of most presidents until Reagan. Our most recent presidents are more visible to the participants, and it’s hard to resist one’s personal preferences. Reagan, both Bushes, Obama, and Biden show sharp partisan divides. But not Trump, rated the worst president by liberals (really? worse than Wilson?) and 3rd worst by conservatives.

In his 2009 book Recarving Rushmore: Ranking the Presidents on Peace, Prosperity, and Liberty, Ivan Eland gives high grades to presidents who left the American people alone to enjoy peace and prosperity, such as Grover Cleveland, Martin Van Buren, and Rutherford B. Hayes. The fact that you can’t remember what any of those presidents did is a plus. At the bottom he places Wilson, Truman, McKinley, Polk, and George W. Bush. If you’ve ever wondered whether a particular president deserves the respect he seems to get, you might take a look at Libertarianism.org’s “Everything Wrong with the Presidents.”

Lately we’ve had a string of presidents who thought their office was invested with kingly powers. Both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama used executive orders to grant themselves extraordinary powers to deal with terrorism. Lawmaking by the president, through executive orders, is a clear usurpation of both the legislative powers granted to Congress and the powers reserved to the states. The president’s principal duty under the Constitution is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed”—not to make laws, as presidents have increasingly done.

Clinton aide Paul Begala boasted: “Stroke of the pen, law of the land. Kind of cool.” President Barack Obama declared: “We’re not just going to be waiting for legislation.… I’ve got a pen, and I’ve got a phone, and I can use that pen to sign executive orders and take executive actions and administrative actions that move the ball forward.” President Donald Trump upped the ante: “I have an Article II, where I have the right to do whatever I want as president.”

President Biden has presumed to use executive power to forgive student debt, support “clean energy,” impose an eviction moratorium, and more. But that’s not enough for his “progressive” supporters, who have urged him to impose a comprehensive legislative agenda by executive order, acting once again as if Congress’s unwillingness to pass the president’s agenda is justification for executive fiat.

Thus have presidents openly dismissed the legislative process. They should take a look at the White House’s own website, where they would read: “Under Article II of the Constitution, the President is responsible for the execution and enforcement of the laws created by Congress.” Exactly. Not to make the laws, but to execute and enforce them. No matter what agenda the president seeks to impose by executive order, Congress should stop him. The body to which the Constitution delegates “all legislative powers herein granted” must assert its authority.

On this Presidents’ Day—which is officially Washington’s Birthday—think of the example set by George Washington. Twice he gave up power, setting a standard for future presidents. And, to quote WhiteHouse.gov again, as president “He did not infringe upon the policy making powers that he felt the Constitution gave Congress.”

Posted on February 20, 2024 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz gives a speech, “The Rise of Illiberalism in the Shadow of Liberal Triumph,” at LibertyCon International 2024 hosted by Students for Liberty

Posted on February 2, 2024 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Solution to Every Problem Is Not Another Government Program

The Washington Post reports:

[Maryland Gov. Wes] Moore is not close to accomplishing his moonshot goals — among them, eliminating child poverty and reducing the overincarceration of young Black men — but has faced little criticism for it. He heads into a second year with less‐favorable financial headwinds and even more aspirations. Among them: growing the state’s economy, helping women who want to rejoin the workforce and fixing a yawning affordable housing crisis — complex problems that take time and deep resources to address.

Sigh. So many assumptions built into that last phrase, “complex problems that take time and deep resources to address.” Time, maybe. Change takes time. But more resources than the state of Maryland has? Not really.

Take a look at the problems:

- eliminating child poverty. The best way to eliminate poverty is to eliminate the regulations that block investment, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Growth means more and better jobs.

- reducing the overincarceration of young Black men. Repeal laws against the use and sale of drugs, and other victimless crimes, and then you won’t be arresting and incarcerating so many young Black men. Save jail for violent or dangerous criminals. No new resources needed. Indeed, resources are freed up for other purposes. Also, Baltimore in particular has terrible schools. Give families, including poor families, a chance to choose better schools.

- growing the state’s economy. Deregulation and lower taxes would help. Take a look at the policies of the states that score highest on economic freedom, New Hampshire, Florida, and South Dakota, or even number 18, Virginia.

- helping women who want to rejoin the workforce. The deregulations noted above will mean more jobs for everyone.

- fixing a yawning affordable housing crisis. Let. People. Build. More. Housing.

So many problems, and so many people whose immediate instinct is, “What new government program or agency can solve this problem that government programs have not solved in years?” Try asking, “Are there government programs that are preventing people from improving this situation?”

Posted on January 22, 2024 Posted to Cato@Liberty

To Save the World, Fight for Liberalism

For thousands of years, most of recorded history, the world was characterized by power, privilege, and oppression. Life for most people was, in the phrase of Thomas Hobbes, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

leadAnd then something changed. In the 17th century, the Scientific Revolution emerged out of a new, more empirical way of doing science. And that led into the Enlightenment beginning late that century. In his book Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker identifies four themes of the Enlightenment: reason, science, humanism, and progress.

Liberalism arose in that environment. People began to question the role of the state and the established church. They argued for liberty for all based on the equal natural rights and dignity of every person. John Locke, often regarded as the father of liberalism, argued in his Second Treatise of Government that every person has a property in his own person and in “the work of his hands”; that government is formed to protect life, liberty, and property and is based on the consent of the governed; and that if government exceeds its proper role, the people are entitled to replace it.

As the economist and intellectual historian Daniel Klein has shown, in the 1770s writers began using such terms as “liberal policy,” “liberal plan,” “liberal system,” “liberal views,” “liberal ideas,” and “liberal principles.” Adam Smith was another founding figure of liberalism. In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, he wrote about “allowing every man to pursue his own interest his own way, upon the liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice.” The term “liberalism” came along about a generation later.

The year 1776, of course, also saw the publication of the most eloquent piece of liberal or libertarian writing ever, the American Declaration of Independence, which concisely laid out Locke’s analysis of the purpose and limits of government.

Liberalism was emerging in continental Europe, too, in the writings of Montesquieu and Benjamin Constant in France, Wilhelm von Humboldt in Germany, and others. In the 1820s the representatives of the middle class in the Spanish Cortes, or parliament, came to be called the Liberales. They contended with the Serviles (the servile ones), who represented the nobles and the absolute monarchy. The term Serviles, for those who advocate state power over individuals, unfortunately didn’t stick. But the word “liberal,” for the defenders of liberty and the rule of law, spread rapidly. The Whig Party in England came to be called the Liberal Party. Today we know the philosophy of John Locke, Adam Smith, the American Founders, and John Stuart Mill as liberalism.

The Liberal 19th Century

In both the United States and Europe the century after the American Revolution was marked by the spread of liberalism. The ancient practices of slavery and serfdom were finally ended though some of their unjust structures stubbornly persist. Written constitutions and bills of rights protected liberty and guaranteed the rule of law. Guilds and monopolies were largely eliminated, with all trades thrown open to competition based on merit. Freedom of the press and of religion was greatly expanded, property rights were made more secure, and international trade was freed. After the defeat of Napoleon, Europe enjoyed a century of relative peace.

That liberation of human creativity unleashed astounding scientific and material progress. The Nation magazine, which was then a truly liberal journal, looking back in 1900, wrote, “Freed from the vexatious meddling of governments, men devoted themselves to their natural task, the bettering of their condition, with the wonderful results which surround us.” The technological advances of the liberal 19th century are innumerable: the steam engine, the railroad, the telegraph, the telephone, electricity, the internal combustion engine. Thanks to such innovations and an explosion of entrepreneurship, in Europe and America the great masses of people began to be liberated from the backbreaking toil that had been the natural condition of humankind since time immemorial. Infant mortality fell and life expectancy began to rise to unprecedented levels. A person looking back from 1800 would see a world that for most people had changed little in thousands of years; by 1900 the world was unrecognizable.

The Turn Away from Liberalism

Toward the end of the 19th century, classical liberalism began to give way to new forms of collectivism and state power. That Nation editorial went on to lament that “material comfort has blinded the eyes of the present generation to the cause which made it possible” and that “before [statism] is again repudiated there must be international struggles on a terrific scale.”

From the disastrous World War I on, governments grew in size, scope, and power. Exorbitant taxation, militarism, conscription, censorship, nationalization, and central planning signaled that the era of liberalism, which had so recently supplanted the old order, was now itself supplanted by the era of the megastate.

Through the Progressive Era, World War I, the New Deal, and World War II, there was tremendous enthusiasm for bigger government among American intellectuals. Herbert Croly, the first editor of the New Republic, wrote in The Promise of American Life that that promise would be fulfilled “not by … economic freedom, but by a certain measure of discipline; not by the abundant satisfaction of individual desires, but by a large measure of individual subordination and self‐denial.”

The Changing Meaning of Liberal

Around 1900 even the term “liberal” underwent a change. People who supported big government and wanted to limit and control the free market started calling themselves liberals. The economist Joseph Schumpeter noted, “As a supreme, if unintended, compliment, the enemies of private enterprise have thought it wise to appropriate its label.” Scholars began to refer to the philosophy of individual rights, free markets, and limited government—the philosophy of Locke, Smith, and Mill—as classical liberalism. Some liberals, including F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman, continued to call themselves liberals. But others came up with a new word, libertarian.

In much of the world even today the advocates of liberty are still called liberals. In South Africa the liberals, such as Helen Suzman, rejected the system of racism and economic privilege known as apartheid in favor of human rights, nonracial policies, and free markets. In China, Russia, and Iran, liberals are those who want to replace totalitarianism in all its aspects with the liberal system of free markets, free speech, and constitutional government. Even in Western Europe, the term liberal still indicates at least a fuzzy version of classical liberalism. German liberals, for instance, usually to be found in the Free Democratic Party, oppose the socialism of the Social Democrats, the corporatism of the Christian Democrats, and the paternalism of both.

For all the growth of government in the past century, liberalism remains the basic operating system of the United States, Europe, and many other parts of the world, even if it is facing attacks. Those countries broadly respect such basic liberal principles as private property, markets, free trade, the rule of law, government by consent of the governed, constitutionalism, free speech, free press, religious freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, peace, and a generally free and open society—but not without plenty of arguments, of course, over the scope of government and the rights of individuals, from taxes and the welfare state to drug prohibition and war. But as Brian Doherty wrote in Radicals for Capitalism, his history of the libertarian movement, we live in a liberal world that runs on a “general belief in property rights and the benefits of liberty.”

America’s Liberal Heritage

And that is certainly true in the United States. The great American historian Bernard Bailyn wrote:

,The major themes of eighteenth‐century [English] radical libertarianism [were] brought to realization here. The first is the belief that power is evil, a necessity perhaps but an evil necessity; that it is infinitely corrupting; and that it must be controlled, limited, restricted in every way compatible with a minimum of civil order. Written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, and courts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express the profound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of the American Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanent legacy ever after.

Through all our many political fights, especially after the abolition of slavery, American debate has taken place within a broad liberal consensus.

Modern American politics can be traced to the era of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, when “liberalism” came to mean activist government, theoretically to help the poor and the middle class—taxes, transfer programs, and regulation—plus a growing concern for civil rights and civil liberties. Race relations, which had taken a turn for the worse in the Progressive Era, with Woodrow Wilson’s resegregation of the federal workforce, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, and the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, began to improve after World War II with the desegregation of the armed forces and federal employment and subsequent moves to undo legal segregation. A new opposition arose, a conservative movement led by William F. Buckley Jr., Sen. Barry Goldwater, and President Ronald Reagan. That conservative movement preached a gospel of free markets, a strong national defense, and “traditional values,” which often meant opposition to civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights.

And those were the opposing factions in American politics from the 1960s to 2015. But Donald Trump changed that picture. He didn’t really campaign on free markets, traditional values, and a strong national defense. He emphasized his opposition to free trade and immigration, was largely indifferent to abortion and gay rights, and engaged in open racial and religious scapegoating. That was a big shift from the Republican party shaped by Ronald Reagan, but Trump remade the GOP in his image.

Now we have Democrats moving left in all the wrong ways—far more spending than even the Obama administration, openly socialist officials, and aggressive efforts to restrict free speech in the name of fighting “hate speech.” Meanwhile, Republicans are moving to the wrong kind of right—a culture war pitting Americans against Americans and a new willingness to use state power to hurt their opponents, including private businesses.

The Classical Liberal Center

Where does that leave classical liberals with libertarian sensibilities who wish to tightly restrain government power? Well, right where we’ve always been: advocating the philosophy of freedom—economic freedom, personal freedom, human rights, political freedom.

But if the hard left becomes more hostile to capitalism and abandons free speech, and Republicans double down on aggressive cultural conservatism and protectionism, maybe there’s room for a new political grouping, which we might call the classical liberal center.

Pundits talk a lot about “fiscally conservative and socially liberal” swing voters, and a Zogby poll commissioned by the Cato Institute once found that 59% of Americans agreed that they would describe themselves that way. Most Americans, at least before the culture wars intensified and negative polarization set in, were content with both the cultural liberations of the 1960s and the economic liberations begun in the 1980s.

That broadly “liberal” center is politically homeless today. If we approach politics and policy reasonably, that combination on economy and culture could provide a nucleus for that broad center of peaceful and productive people in a society of liberty under law.

The Classical Liberal Challenge

As bleak as things sometimes seem in the United States, there are definitely worse problems in the world. In too much of the world, ideas we thought were dead are back: socialism and protectionism and ethnic nationalism, even “national socialism,” authoritarianism on both the left and the right. We see this in Russia and China, of course, but not only there; also in relatively liberal democratic countries such as Turkey, Hungary, Venezuela, Mexico, the Philippines, maybe India. A far‐right candidate—anti-immigration, anti‐globalization, anti–free trade, anti‐privatization, anti–pension reform—came too close for comfort to the presidency of France.

There are multiple and competing threats to liberty: identity politics and the intolerant left; populism and the yearning for strongman rule that invariably accompanies it; and various forms of authoritarian nationalisms.

People who oppose these ideas need to develop a defense of liberty, equality, and democracy. And principled classical liberals are well suited to do that.

In 1997, Fareed Zakaria wrote:

,Consider what classical liberalism stood for in the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was against the power of the church and for the power of the market; against the privileges of kings and aristocracies and for dignity of the middle class; against a society dominated by status and land and in favor of one based on markets and merit; opposed to religion and custom and in favor of science and secularism; for national self‐determination and against empires; for freedom of speech and against censorship; for free trade and against mercantilism. Above all, it was for the rights of the individual and against the power of the church and the state.

And, he said, correctly, it won a sweeping victory against “an order that had dominated human society for two millennia—that of authority, religion, custom, land, and kings.”

Committed classical liberals are tempted to be too depressed. We read the morning papers, or watch the cable shows, and we think the world is indeed on “the road to serfdom.” But we should reject a counsel of despair. We’ve been fighting ignorance, superstition, privilege, and power for many centuries. Our classical liberal forebears have won great victories. The fight is not over, but liberalism remains the only workable operating system for a world of peace, growth, and progress.

Posted on January 2, 2024 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz’s blog post, “Scott Walker Defends Corporate Welfare for NBA,” is cited on WPGP’s The John Steigerwald Show

Posted on December 12, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

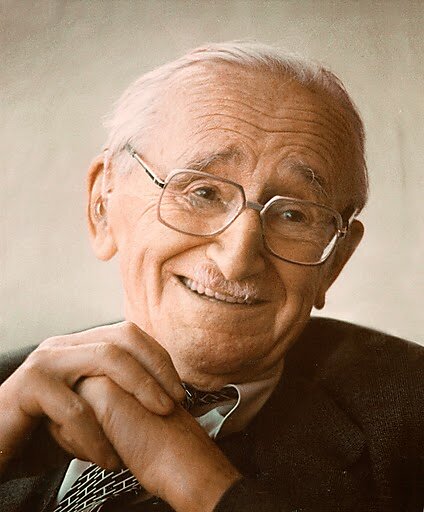

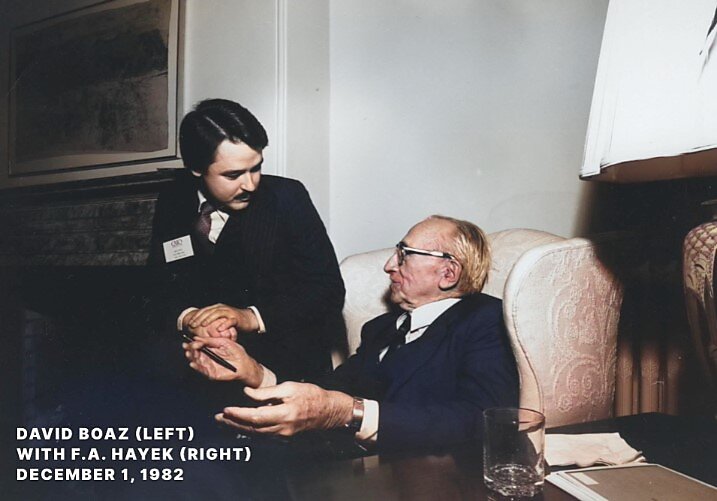

When Hayek Came to Cato

On December 1, 1982, F. A. Hayek became Cato’s first Distinguished Lecturer. Cato had supported his work for several years, and he was later named a Distinguished Senior Fellow — an honor to be sure, but not quite up to the level of his 1974 Nobel Prize.

Hayek’s life spanned the 20th century, from 1899 to 1992. In his youth he thought he saw liberalism dying in nationalism and war. Thanks partly to his own efforts, in his old age he was heartened by the revival of free‐market liberalism. John Cassidy wrote in the New Yorker that “on the biggest issue of all, the vitality of capitalism, he was vindicated to such an extent that it is hardly an exaggeration to refer to the twentieth century as the Hayek century.”

Back in 2010 the New York Times said that the Tea Party “has reached back to dusty bookshelves for long‐dormant ideas. It has resurrected once‐obscure texts by dead writers [such as] Friedrich Hayek’s “Road to Serfdom” (1944).” I responded at the time,

So that’s, you know, “long‐dormant ideas” like those of F. A. Hayek, the winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, who met with President Reagan at the White House, whose book The Constitution of Liberty was declared by Margaret Thatcher “This is what we believe,” who was described by Milton Friedman as “the most important social thinker of the 20th century” and by White House economic adviser Lawrence H. Summers as the author of “the single most important thing to learn from an economics course today,” who is the hero of The Commanding Heights, the book and PBS series by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, and whose book The Road to Serfdom has never gone out of print and has sold 100,000 copies this year.

On the occasion of Hayek’s 100th birthday, Tom G. Palmer summed up some of his intellectual contributions:

Hayek may have made his greatest contribution to the fight against socialism and totalitarianism with his best‐selling 1944 book, The Road to Serfdom. In it, Hayek warned that state control of the economy was incompatible with personal and political freedom and that statism set in motion a process whereby “the worst get on top.”

But not only did Hayek show that socialism is incompatible with liberty, he showed that it is incompatible with rationality, with prosperity, with civilization itself. In the absence of private property, there is no market. In the absence of a market, there are no prices. And in the absence of prices, there is no means of determining the best way to solve problems of social coordination, no way to know which of two courses of action is the least costly, no way of acting rationally. Hayek elaborated the insights of the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, whose 1922 book Socialism offered a brilliant refutation of the dreams of socialist planners. In his later work, Hayek showed how prices established in free markets work to bring about social coordination. His essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” published in the American Economic Review in 1945 and reprinted hundreds of times since, is essential to understanding how markets work.

But Hayek was more than an economist. As I’ve written before, he also published impressive works on political theory and psychology. He’s like Marx, only right. Tom Palmer noted:

Building on his insights into how order emerges “spontaneously” from free markets, Hayek turned his attention after the war to the moral and political foundations of free societies. The Austrian‐born British subject dedicated his instant classic The Constitution of Liberty “To the unknown civilization that is growing in America.” Hayek had great hopes for America, precisely because he appreciated the profound role played in American popular culture by a commitment to liberty and limited government. While most intellectuals praised state control and planning, Hayek understood that a free society has to be open to the unanticipated, the unplanned, the unknown. As he noted in The Constitution of Liberty, “Freedom granted only when it is known beforehand that its effects will be beneficial is not freedom.” The freedom that matters is not the “freedom” of the rulers or of the majority to regulate and control social development, but the freedom of the individual person to live his own life as he chooses. The freedom of the individual to break old molds, to create new things, and to test new paths is the mark of a progressive society: “If we proceed on the assumption that only the exercises of freedom that the majority will practice are important, we would be certain to create a stagnant society with all the characteristics of unfreedom.”

Reagan and Thatcher may have admired Hayek, but he always insisted that he was a liberal, not a conservative. He titled the postscript to The Constitution of Liberty “Why I Am Not a Conservative.” He pointed out that the conservative “has no political principles which enable him to work with people whose moral values differ from his own for a political order in which both can obey their convictions. It is the recognition of such principles that permits the coexistence of different sets of values that makes it possible to build a peaceful society with a minimum of force. The acceptance of such principles means that we agree to tolerate much that we dislike.” He wanted to be part of “the party of life, the party that favors free growth and spontaneous evolution.” And I recall an interview in a French magazine in the 1980s, which I can’t find online, in which he was asked if he was part of the “new right,” and he quipped, “Je suis agnostique et divorcé.”

Hayek lived long enough to see the rise and fall of fascism, national socialism, and Soviet communism. In the years since Hayek’s death economic freedom around the world has been increasing (until a hopefully temporary dip during the Covid pandemic), and liberal values such as human rights, the rule of law, equal freedom under law, and free access to information have spread to new areas. But today liberalism is under challenge from such disparate yet symbiotic ideologies as resurgent leftism, right‐wing authoritarian populism, and radical political Islamism. I am optimistic because I think that once people get a taste of freedom and prosperity, they want to keep it. The challenge for Hayekian liberals is to help people understand that freedom and prosperity depend on liberal values, the values explored and defended in his many books and articles.

Hayek came to Cato once more, for a small lunch. I have a picture from that event that I especially like because it looks like it’s just myself and Hayek at the table. Except for the dozen or so wine and water glasses of tablemates who weren’t in the camera shot.

“Exclusive Interview with F. A. Hayek,” Cato Policy Report, vol. 6, no. 3, May/June 1984.

“An Interview With F. A. Hayek,” Cato Policy Report, vol. 5, no. 2, February 1983.

Posted on December 1, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

44 Years of Cato Policy Report

This is the last issue of Cato Policy Report (CPR) after 44 years. In that time, we have presented original articles on policy, history, law, economics, international affairs, and the principles of liberty. We have covered major Cato Institute events, including policy conferences such as “The Search for Stable Money” in 1983—featuring James Buchanan, Karl Brunner, Allan Meltzer, Fritz Machlup, and Anna Schwartz—our conferences in Moscow and Shanghai, and Milton Friedman Prize dinners.

leadWe have published some 301 issues, of which I edited 276 after joining Cato in 1981. Looking back, I remember a wide range of topics and some fascinating essays. The very first issue featured “Social Security: Has the Crisis Passed?” by Carolyn L. Weaver. That was appropriate since reforming the Social Security program became a signature Cato issue that generated books, conferences, and continuing engagement with policymakers who mostly didn’t want to face the problem.

William A. Niskanen, then a member of President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, made his first appearance in CPR in May 1983 when he commented on Lawrence H. White’s book Free Banking in Britain. I still remember one point he made in his talk: the burden of proof in policy ought to rest with those “who propose restrictions on consensual relations of any kind.” But in practice, the burden of proof is on those who are proposing change—and within the government, on those who propose to reduce government’s discretion.

Two years later, when Niskanen became Cato’s chair, he gave an inaugural lecture, “The Growth of Government.” I remember the way he set out Cato’s distinctive perspective:

,We will differ from the dominant political traditions primarily when they try to use the powers of the state to impose their particular values on the larger community. We will oppose contemporary liberals when they fail to distinguish between a virtue and a requirement. We will oppose contemporary conservatives when they fail to distinguish between a sin and a crime.

Nineteen ninety‐two was a big year for CPR. In successive issues, we published lead articles by P. T. Bauer, later the first recipient of the Milton Friedman Prize; Norman Macrae, the longtime deputy editor of The Economist; and the great philosopher Karl Popper. That last was one of my great accomplishments as editor. I had read that a paper by the ailing Popper had been given at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association. I wrote to the scholar who had presented it for him and then wrote to Popper at his home in New Zealand, and I got permission to publish his paper. In it, he wrote about F. A. Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and the Mont Pelerin Society, but most especially how Hayek was right to warn that socialist planning could only be implemented “by force, by terror, by political enslavement”—and thus, Popper added, the Soviet Union became an empire ruled by lies.

Over the years, we published other great thinkers: Robert Nozick on why intellectuals hate capitalism, Thomas Sowell on the economics and politics of race, Nat Hentoff on the First Amendment, James Buchanan on constitutional political economy, Deirdre McCloskey on bourgeois virtues, Ronald Coase on China, Steven Pinker on the Enlightenment, and Clarence Thomas’s powerful dissent in the Supreme Court’s 2005 medical marijuana case.

And, of course, most of our own great Cato scholars contributed to CPR. Tom G. Palmer wrote on a wide variety of topics—infrastructure, attacks on libertarianism, misconceptions about individualism, and modern threats to liberty. Doug Bandow reported on his trip to North Korea, Julian Sanchez on Edward Snowden’s revelations, Peter Ferrara and Michael Tanner on needed changes to Social Security, Roberto Salinas‐León on Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s “fourth transformation” of Mexico, and Clark Neily on “our broken justice system.”

From time to time, we have delved into historical topics, partly because people get much of their understanding of government and policy from history. Jim Powell took aim at Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt, while Michael Chapman excoriated Theodore Roosevelt. Brian Domitrovic celebrated the tax revolt of the 1970s and 1980s. George H. Smith pondered what Stanford should teach regarding “Western civilization.” Steven Davies traced how the world became modern.

Editing Cato Policy Report all these years has been a great opportunity for me to engage with policy and ideas. I hope the editors of Cato’s new magazine will have an equally stimulating experience.

Posted on November 3, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

King Biden Issues Another Decree

Newspaper headlines proclaim that President Biden has issued a “massive, sweeping, wide‐ranging” executive order on artificial intelligence. And no one seems to be saying that whatever the content of the order is, “massive, sweeping, wide‐ranging” regulations should not be issued by one man.

President Biden, members of Congress, and the judiciary should take a look at the White House’s own website, where they would read: “Under Article II of the Constitution, the President is responsible for the execution and enforcement of the laws created by Congress.” Not to make the laws, but to execute and enforce them. If AI needs government attention, it should come from Congress.

Biden is not the first president to believe that his office was invested with kingly powers. Both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama used executive orders to grant themselves extraordinary powers to deal with terrorism. Lawmaking by the president, through executive orders, is a clear usurpation of both the legislative powers granted to Congress and the powers reserved to the states.

Clinton aide Paul Begala once boasted: “Stroke of the pen, law of the land. Kind of cool.” President Obama declared: “We’re not just going to be waiting for legislation.… I’ve got a pen, and I’ve got a phone, and I can use that pen to sign executive orders and take executive actions and administrative actions that move the ball forward.” President Donald Trump upped the ante: “I have an Article II, where I have the right to do whatever I want as president.”

One of the great concerns of the Founders was to rein in executive power. Thus they wrote a Constitution to divide and limit the powers of all elected officials. But they thought that each branch would be jealous of its own authority and would not tolerate a usurpation of its power by the other branches. Somehow Congress and the courts have lost their taste for conflict with the executive.

No matter what agenda the president seeks to impose by executive order, Congress should stop him. The body to which the Constitution delegates “all legislative powers herein granted” must assert its authority. In a constitutional republic, one man should not have kingly powers — and the Constitution doesn’t grant them to him.

Posted on November 1, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

China’s Heroic Unofficial Historians

Authoritarian—and not just authoritarian—governments typically see national history as an important way to shore up support for the regime. China is probably the most prominent example of that right now, as Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party reinforce their efforts to teach every Chinese citizen the glories of the party’s history and to conceal the truth about such crimes as the land‐reform campaigns of the early fifties, the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward, and the Tiananmen Square massacre. But a new book reveals the efforts of unofficial historians to make sure the truth is not lost.

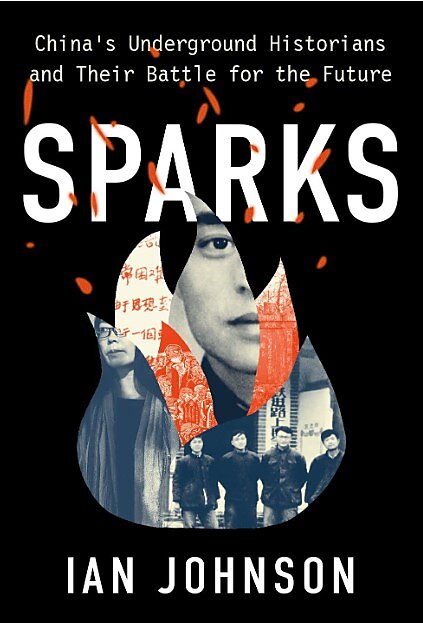

The book by Ian Johnson is Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future. Ian Buruma has a long and informative review in the New Yorker:

Johnson’s underground historians are mostly concerned with unearthing and keeping alive forbidden memories of the past. Official Party history, imposed on China’s population, is also a matter of official forgetting. Many people born in China after 1989 have never heard of the Tiananmen massacre. Many of the young people who lived through the Cultural Revolution, in the nineteen‐sixties and early seventies, would have had limited knowledge of the Great Leap Forward, in the late fifties and early sixties, when Mao’s crackpot schemes for industrial and agricultural transformation caused tens of millions of deaths from starvation. And many of those who starved may not have been fully aware of the land‐reform campaigns of the early fifties, when vast numbers of people were murdered as class enemies, because they owned some land (as Mao’s father did, but that is a fact Party ideologues prefer to keep quiet).

The book’s title comes from a secretly mimeographed magazine, Spark, that began in 1960. It lasted only two issues, “and some of the contributors were executed as ‘counter‐revolutionaries’ after spending years in prison under horrifying conditions.” But it inspired “the writers, the scholars, the poets, and the filmmakers who found the courage to challenge Communist Party propaganda.”

Johnson describes efforts over many decades and also ongoing work today. Of course, “None of this work can be released in China.… But Johnson’s underground historians are mostly concerned with unearthing and keeping alive forbidden memories of the past. Official Party history, imposed on China’s population, is also a matter of official forgetting.”

It’s an inspiring story. And of course China is not the only country trying to craft an official history that may veer far from the truth. The Soviet Union pioneered official history and official forgetting before Mao came to power and before George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty‐Four. After the fall of the USSR the dissident and human rights activist Vladimir Bukovsky, who late in life was a Cato senior fellow, devoted much of his efforts, along with organizations as Memorial, to exposing the crimes of the Communist Party.

Of course, history is a concern of liberal and democratic countries as well. Shakespeare wrote plays that promoted the claims and the achievement of the Tudor dynasty, which was most pleasing to Queen Elizabeth I. The American Founders believed that the study of history is our best guide to the present and the future. The authors of the Federalist Papers wrote of history as “the oracle of truth” and “the least fallible guide of human opinions.” From their study of history they learned of the ancient rights of Englishmen, the importance of individual virtue in preserving freedom, and the dangers of power and thus the necessity of constraining and dividing it.

History helps us to understand the development of our civilization, including the ideas that shape it. Often the ideas that we now regard as universal principles arose in response to particular circumstances. Magna Carta and similar medieval charters reflect the struggle to constrain the power of kings. From such guarantees of specific liberties, eventually liberty developed. The rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights reflected particular historical experiences: with religious wars, censorship, confiscation of property, the Star Chamber, and the constant tendency of government to seek more power.

People get much of their understanding of government and policy from history. The way we view the Constitution, slavery, Jim Crow, the industrial revolution, the robber barons, the New Deal, and other historical events shapes our view of the present. And in a liberal society we’re not always going to agree on the lessons or even the facts of history.

Scholars such as Frances Fitzgerald have written about past battles over how to tell the American story. And of course we’re having heated disputes today over how to understand and teach American history.

But for now I want to focus on the courageous efforts of Chinese citizens who have given so much to keep the truth alive. And I’ll also note that we at the Cato Institute have done our very little bit to introduce dissident ideas into China.

During the post‐Mao opening Cato held conferences on liberty, limited government, and free markets in China in 1988, 1997, 2000, and 2001. The 1988 conference, featuring Milton Friedman, numerous Chinese scholars, and a Friedman meeting with Premier Zhao Ziyang, was surely the first conference on market liberalism in Chinese history. Papers from the conference were published in both English and Chinese (English title Economic Reform in China), as were papers from the 1997 conference (China in the New Millennium). Several Cato books have been published in China: my Libertarianism: A Primer (later updated as The Libertarian Mind) in 2012, Johan Norberg’s books In Defense of Global Capitalism and Progress, Randal O’Toole’s Gridlock and The Best‐Laid Plans, and just last month the Cato Handbook for Policymakers.

Ian Johnson is telling an important story of heroic Chinese people who for more than 60 years have been making sure historical truth is not lost in a great country.

Posted on October 6, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

In Defense of Globalization

We hear a lot of debates these days about globalization. What is globalization? Globalization is simply the process of the free movement of goods, capital, people, and ideas around the world and across borders.

leadGlobalization is a great boon to the world. It means more specialization and division of labor, which are vital components of economic progress. It makes rich countries richer and brings poor countries out of crushing poverty.

Market reforms within countries are important, but becoming part of the global division of labor has been crucial to the rise of middle classes in China, India, Mexico, Chile, and eastern Europe. The proportion of the world population in extreme poverty, i.e. who consume less than $1.90 a day, adjusted for local prices, declined from 36 percent in 1990 to 10 percent in 2015.

That’s the biggest story of the epoch, maybe the greatest achievement in human history. As Max Roser of Our World in Data points out, newspapers could have run the headline NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN EXTREME POVERTY FELL BY 137,000 SINCE YESTERDAY every day for 25 years.

But people don’t know this!

In a recent poll 66 percent of Americans thought world poverty had doubled. A free economy is not a zero‐sum game. Trade and specialization are win‐win. The pie grows for everyone.

And what’s the alternative? Self‐sufficiency? As Leonard Read and Milton Friedman pointed out, no single person on earth can make something as simple as a pencil. You’d need wood from Oregon, graphite from Sri Lanka, wax from Mexico, castor oil from the tropics, and rubber from Indonesia. Not to mention factories to combine those elements into a pencil.

Andy George, host of the Youtube show How to Make Everything, decided to make a chicken sandwich from scratch. It turned out to mean spending six months and $1,500 growing a garden, turning ocean water into salt, making cheese, and killing a chicken all so he could take a bite of a sandwich truly made from scratch.

From both President Trump and President Biden, we hear a lot about “Buy American.” That’s almost as senseless as making a chicken sandwich from scratch. The raw materials, the labor, and the technology necessary to produce the elements of modern life are spread across the globe. It would be vastly more expensive for any country – the United States, India, Nigeria – to refuse to trade with people in other countries to produce goods cheaply and efficiently.

And if it makes sense to “buy American,” why not “buy California”? “Buy Los Angeles”? “Keep our money here in Hollywood!”

As trade specialist Dan Ikenson observed in 2009, most of our modern products should be labeled “Made on Earth,” produced by “a truly global division of labor, [with] opportunities for specialization, collaboration, and exchange on scales once unimaginable.”

In the past generation globalization has brought more people into the world economy, and billions of people are rising out of poverty.

At the same time Enlightenment values of tolerance and human rights are spreading to more parts of the world, with particular emphasis on the rights of women, racial and religious minorities, and gay and lesbian people.

The Internet is giving people more information, more ways to connect, more commercial opportunities, and more choice. Despite what we may be led to think from the flood of information about the world, we are probably living in the most peaceful era in history.

But economic progress inevitably means change. And change can be painful. Think of the transition from 90 percent of American workers working on farms, to about 2 percent today. Now we’re in similar transitions from manufacturing to services and robots.

Some people get hurt in such transitions. They may lose their jobs, or their businesses, or see their own wages not increasing as fast as other people’s, or simply fear that such consequences may happen. And when people perceive a decline in their income or their relative social status, they often want help, and they want to blame someone. That can mean both a demand for government programs and the scapegoating of villains – whether it’s the bankers, the 1 percent, the Jews, the immigrants, the Mexicans, or whoever – just the opposite of the individualist liberalism that gave us the unprecedented progress we have experienced.

We’ve seen a rise of populist and illiberal forces in countries around the world, on both left and right – with threats to liberty, democracy, trade, growth, and even peace. All the bad new ideas – socialism, protectionism, industrial policy — are really bad old ideas. Libertarians and classical liberals have been fighting them off for more than 200 years, and we need to keep doing it.

Posted on September 22, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty