Boston Beats Beijing in Olympics Contest

News comes this morning that Beijing has been awarded the 2022 Winter Olympics, beating out Almaty, Kazakhstan. Which touches on a point I made in this morning’s Boston Herald:

Columnist Anne Applebaum predicted a year ago that future Olympics would likely be held only in “authoritarian countries where the voters’ views will not be taken into account” — such as the two bidders for the 2022 Winter Olympics, Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Fortunately, Boston is not such a place. The voters’ views can be ignored and dismissed for only so long.

Indeed, Boston should be celebrating more than Beijing this week. A small band of opponents of Boston’s bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics beat the city’s elite – business leaders, construction companies, university presidents, the mayor and other establishment figures – because they knew what Olympic Games really mean for host cities and nations:

E.M. Swift, who covered the Olympics for Sports Illustrated for more than 30 years, wrote on the Cognoscenti blog a few years ago that Olympic budgets “always soar.”

“Montreal is the poster child for cost overruns, running a whopping 796 percent over budget in 1976, accumulating a deficit that took 30 years to repay. In 1996 the Atlanta Games came in 147 percent over budget. Sydney was 90 percent over its projected budget in 2000. And the Athens Games cost $12.8 billion, 60 percent over what the government projected.”

Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University, the world’s leading expert on megaprojects, and his co-author Allison Stewart found that Olympic Games differ from other such large projects in two ways: They always exceed their budgets, and the cost overruns are significantly larger than other megaprojects. Adjusted for inflation, the average cost overrun for an Olympics is 179 percent.

Bostonians, of course, had memories of the Big Dig, a huge and hugely disruptive highway and tunnel project that over the course of 15 years produced a cost overrun of 190 percent.

Posted on July 31, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Modern Tea Party Tosses Olympics

Boston, the home of the original American tax revolt, has just dodged a big tax bill by dropping its bid to host the 2024 Summer Olympics.

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 expressed Americans’ growing resentment of British control and their demand for “no taxation without representation.”

After Americans got a sense of what taxation could be like even in a democracy, a tax revolt swept the country, from California’s Proposition 13 in 1978 to Massachusetts’ Proposition 2½ in 1980.

And now Bostonians have once again said “No” to their ruling elite.

As usual, Boston’s Olympics bid was supported by business leaders, construction companies, university presidents, the mayor and other establishment figures.

“‘10 people on Twitter’ manage to best Hub elites.”

The opposition was led largely by three young professionals who set up the No Boston Olympics organization. The construction magnate who headed the local Olympic committee dismissed the group early on, asking: “Who are they and what currency do they have?”

Even at the press conference on the day the city’s bid ended, Mayor Marty Walsh grumbled, “The opposition for the most part is about 10 people on Twitter.”

Apparently those 10 people did a lot of tweeting, to significant effect. After the bid collapsed, WBUR radio noted, “No Boston Olympics was persistent with its message that hosting the games was risky, expensive and would leave taxpayers footing the bill with no economic gains.”

In the station’s monthly polls, opposition to the Olympics rose steadily over the spring from 33 percent to 53 percent.

Some planners and politicos were beside themselves at the withdrawal of the bid. Thomas J. Whalen, a political historian at Boston University, told The New York Times that it sent a discouraging message:

“The time of big dreams, big accomplishments, is over. ‘Think small,’ that’s the mantra for Massachusetts. ‘Limit your dreams’ ” he said. Worse, he said, the end of the bid took away a great opportunity for a “master development plan for Boston.” That is, it took away an opportunity for planners and moguls to tell the people of Boston where and how to live.

The head of the bid committee once lamented that “what bothers me a lot is the decline of pride, of patriotism and love of our country.”

No doubt the East India Company and King George III felt the same way in 1773.

The critics knew something that the Olympic enthusiasts tried to forget: Megaprojects like the Olympics are enormously expensive, always over budget, and disruptive. They leave cities with unused stadiums and other waste.

E.M. Swift, who covered the Olympics for Sports Illustrated for more than 30 years, wrote on the Cognoscenti blog a few years ago that Olympic budgets “always soar.”

“Montreal is the poster child for cost overruns, running a whopping 796 percent over budget in 1976, accumulating a deficit that took 30 years to repay. In 1996 the Atlanta Games came in 147 percent over budget. Sydney was 90 percent over its projected budget in 2000. And the Athens Games cost $12.8 billion, 60 percent over what the government projected.”

Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University, the world’s leading expert on megaprojects, and his co-author Allison Stewart found that Olympic Games differ from other such large projects in two ways: They always exceed their budgets, and the cost overruns are significantly larger than other megaprojects. Adjusted for inflation, the average cost overrun for an Olympics is 179 percent.

Bostonians, of course, had memories of the Big Dig, a huge and hugely disruptive highway and tunnel project that over the course of 15 years produced a cost overrun of 190 percent.

Columnist Anne Applebaum predicted a year ago that future Olympics would likely be held only in “authoritarian countries where the voters’ views will not be taken into account” — such as the two bidders for the 2022 Winter Olympics, Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Fortunately, Boston is not such a place. The voters’ views can be ignored and dismissed for only so long.

The success of the “10 people on Twitter” and the three young organizers of No Boston Olympics should encourage taxpayers in other cities to take up the fight against megaprojects and boondoggles — stadiums, arenas, master plans, transit projects, and indeed other Olympic Games.

Posted on July 31, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cato University 2015: The Libertarian Mind in the 21st Century

From Cato University 2015: Summer Seminar on Political Economy

The Cato Institute’s premier educational event, this annual program brings together outstanding faculty and participants from across the country and, often, from around the globe in order to examine the roots of our commitment to liberty and limited government, and explore the ideas and values on which the American republic was founded.

Posted on July 30, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Trump’s Real Problem

Donald Trump has shot to the top of Republican presidential polls on the strength of his celebrity and his bombastic talk.

Elites on all sides of the political spectrum — liberals, conservatives, and libertarians — are horrified by his ranting about Mexican “rapists.” And he may have shot himself in the foot with his comments about Senator John McCain. But his poll numbers are still up there.

Some voters like his tough talk about illegal immigration. But I think more just prefer businessmen to politicians. Nineteen percent voted for billionaire Ross Perot in 1992, against George Bush and Bill Clinton, even after Perot temporarily withdrew from the race on the very odd grounds that the Bush campaign was trying to disrupt his daughter’s wedding.

Voters sense that businesspeople deal in reality, not rhetoric. They get things done. That’s why there’s always a yearning from someone from outside politics to come in and clean up government.

“Unfortunately, just because a businessman understands making deals and building hotels doesn’t mean he understands economics.”

The website ThinkProgress talked to three Trump voters at the Family Leadership Summit in Iowa, all of whom emphasized that point. “I just think we need a business man to run the country like a business,” Jim Nelle, a small business owner from Winterset, Iowa, said. David Brown, a farmer and investor from New Virginia, Iowa, noted, “We’re not broke, we’re $19 trillion past broke and I believe that he has the business acumen and wisdom to bring the nation back.” And Bill Raine of New Hampton put it simply: “He’s a businessman, he’s not a politician.”

Unfortunately, just because a businessman understands making deals and building hotels doesn’t mean he understands economics. Trump is definitely an example of that.

What he’s really offering is a mixture of nationalism and protectionist economics along with the promise that he’s the guy, the man on a white horse, who can ride into Washington and fix the mess. He dismisses politicians, other candidates, and American negotiators as “stupid people,” “incompetent people,” and “losers.” He boasts of his wealth and promises that he would “kick [the] ass” of El Chapo, the Mexican drug cartel leader who escaped from prison.

Look at his major issues. He’s been barnstorming the country talking about crime by Mexican immigrants, starting with his claim in his announcement speech that “they’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists.” But there’s no evidence for this. Immigrants are about half as likely to be incarcerated as native-born Americans (men aged 18-39 in both cases), and as the number of legal and illegal immigrants rose in the United States between 1990 and 2010, the rates of violent and property crime fell.

You’d think Mr. Trump would be more sympathetic to immigration. His mother was born in Scotland. His grandfather Trump was born in Germany. His first wife Ivana was born in Czechoslovakia, his current wife Melania was born in Yugoslavia. A genealogist writes on About.com, “Donald Trump epitomizes the American immigrant experience.”

Mr. Trump also doesn’t much like free trade. He regularly rails that “China is taking all our jobs.” He laments that we have “thousands of cars, millions of cars coming in…They send cars, we send corn.” Which actually sounds like a pretty good trade.

At his recent FreedomFest speech he complained about call centers in India, asking, “How can it be that far away and they save money?”

No real businessman would ask such a question. If it weren’t cheaper, businesses wouldn’t do it. Labor is expensive in the United States, cheaper in India and China. So jobs that can be done in cheaper locations are done there, and Americans move into higher-value, higher-paying jobs. The average American wage is now $25 per hour. Employees in Indian call centers make about $2 per hour, a good wage in India but not one that many Americans are looking for.

Mr. Trump doesn’t draw on economics to defend his trade position. It’s all about him, the Donald, just being richer and smarter than the politicians: “Free trade is terrible. Free trade can be wonderful if you have smart people. But we have stupid people. Our trade deals have been made by incompetent people.” He, on the other hand, will “make great trade deals.” But deals have to be good for both sides. He knows that when he builds a building. But he wants voters to believe that he can just bludgeon China or Japan into … what? Not sending us cars? Not letting us outsource low-value labor to low-cost workers? He’d be hard-pressed to find any professional economist, Democrat or Republican, to serve in an administration based on such nonsense.

This “all about me” approach extends to most issues. The deficit? He’s promised to end the corporate income tax, cut individual taxes, and cut spending — but without cutting the biggest programs. How will that work? “I am going to save Social Security without any cuts. I know where to get the money from. Nobody else does.”

I could get behind the idea of a businessman instead of a politician. But not this businessman, who offers only insults, secret plans, and a promise to kick everybody else’s ass.

Posted on July 22, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

No Markets, Then No Water. California’s Avoidable Crisis

This is what happens in a world without markets for water, as Eli Saslow reports in the Washington Post:

Their two peach trees had turned brittle in the heat, their neighborhood pond had vanished into cracked dirt and now their stainless-steel faucet was spitting out hot air. “That’s it. We’re dry,” Miguel Gamboa said during the second week of July, and so he went off to look for water….

For a few days now, they had been without running water in the fifth year of a California drought that had finally come to them. First it had devastated the orchards where Gamboa and his wife had once picked grapes. Then it drained the rivers where they had fished and the shallow wells in rural migrant communities. All the while, Gamboa and his wife had donated a little of their hourly earnings to relief efforts in the San Joaquin Valley and offered to share their own water supply with friends who had run out, not imagining the worst consequences of a drought could reach them here, down the road from a Starbucks, in a remodeled house surrounded by gurgling birdbaths and towering oaks.

The article reads like science fiction. And it’s so tragic, because markets could go a long way toward allocating California’s water to its highest-valued uses, as Peter Van Doren and Gary Libecap discussed recently. More Cato studies on water markets here.

Posted on July 21, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cronyism in Maryland

Martin O’Malley, the former governor of Maryland and Democratic presidential candidate, is no Bill and Hillary Clinton, who have made more than $100 million from speeches, much of it from companies and governments who just might like to have a friend in the White House or the State Department. But consider these paragraphs deep in a Washington Post story today about O’Malley’s financial disclosure form:

While O’Malley commanded far smaller fees than the former secretary of state – and gave only a handful of speeches – he also seemed to benefit from government and political connections forged during his time in public service.

Among his most lucrative speeches was a $50,000 appearance at a conference in Baltimore sponsored by Center Maryland, an organization whose leaders include a former O’Malley communications director, the finance director of his presidential campaign and the director of a super PAC formed to support O’Malley’s presidential bid.

O’Malley also lists $147,812 for a series of speeches to Environmental Systems Research Institute, a company that makes mapping software that O’Malley heavily employed as governor as part of an initiative to use data and technology to guide policy decisions.

I scratch your back, you scratch mine. That’s the sort of insider dealing that sends voters fleeing to such unlikely candidates as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

These sorts of lucrative “public service” arrangements are nothing new in Maryland (or elsewhere). In The Libertarian Mind I retell the story of how Gov. Parris Glendening and his aides scammed the state pension system and hired one another’s relatives.

In some countries governors still get suitcases full of cash. Speaking fees are much more modern.

Posted on July 17, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The French Revolution and Modern Liberty

Today the French celebrate the 226th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the date usually recognized as the beginning of the French Revolution. What should libertarians (or classical liberals) think of the French Revolution?

The Chinese premier Zhou Enlai is famously (but apparently inaccurately) quoted as saying, “It is too soon to tell.” I like to draw on the wisdom of another mid-20th-century thinker, Henny Youngman, who when asked “How’s your wife?” answered, “Compared to what?” Compared to the American Revolution, the French Revolution is very disappointing to libertarians. Compared to the Russian Revolution, it looks pretty good. And it also looks good, at least in the long view, compared to the ancien regime that preceded it.

Conservatives typically follow Edmund Burke’s critical view in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. They may even quote John Adams: “Helvetius and Rousseau preached to the French nation liberty, till they made them the most mechanical slaves; equality, till they destroyed all equity; humanity, till they became weasels and African panthers; and fraternity, till they cut one another’s throats like Roman gladiators.”

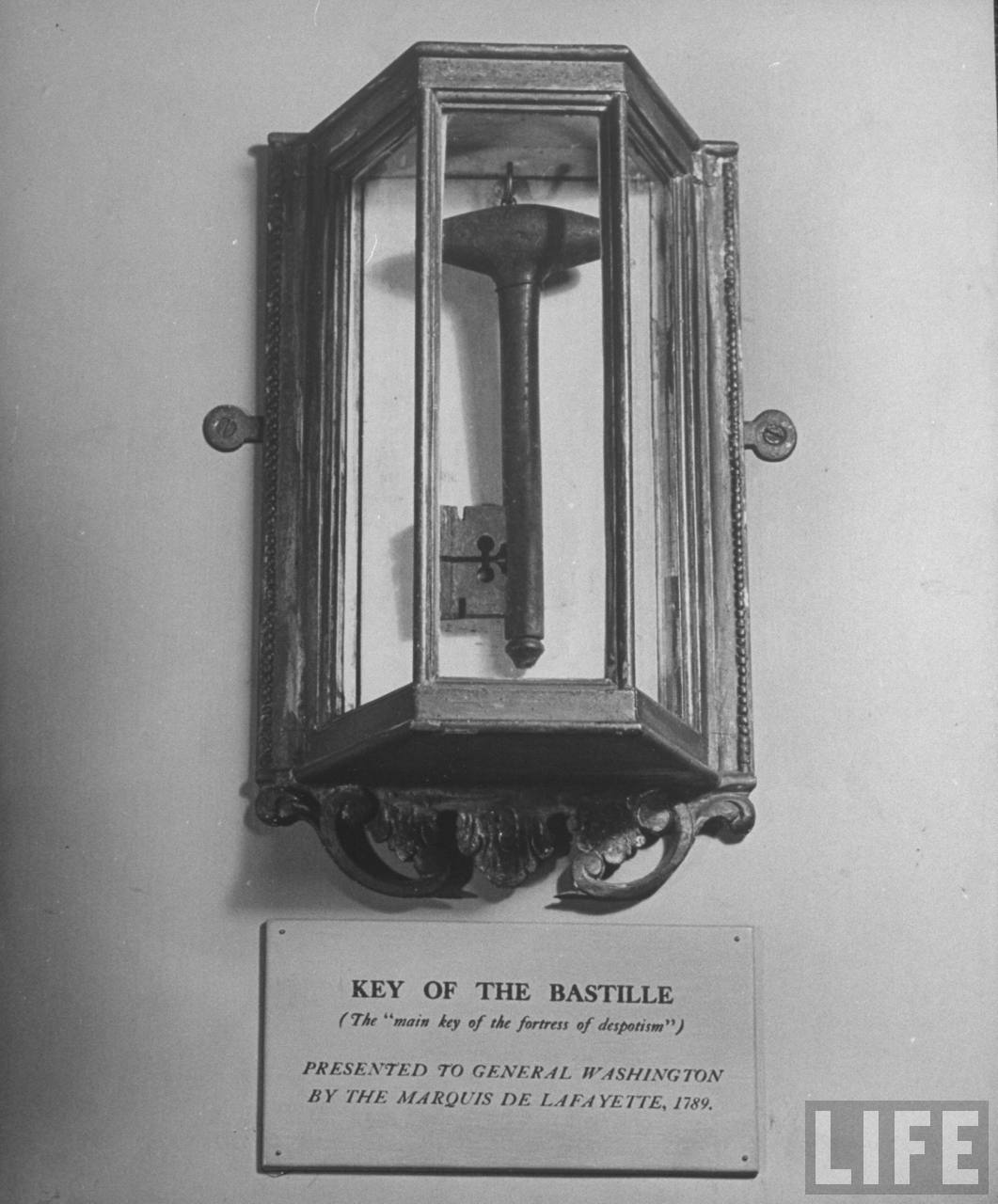

But there’s another view. And visitors to Mount Vernon, the home of George Washington, get a glimpse of it when they see a key hanging in a place of honor. It’s one of the keys to the Bastille, sent to Washington by Lafayette by way of Thomas Paine. They understood, as the great historian A.V. Dicey put it, that “The Bastille was the outward visible sign of lawless power.” And thus keys to the Bastille were symbols of liberation from tyranny.

Traditionalist conservatives sometimes long for “the world we have lost” before liberalism and capitalism upended the natural order of the world. The diplomat Talleyrand said, “Those who haven’t lived in the eighteenth century before the Revolution do not know the sweetness of living.” But not everyone found it so sweet. Lord Acton wrote that for decades before the revolution “the Church was oppressed, the Protestants persecuted or exiled, … the people exhausted by taxes and wars.” The rise of absolutism had centralized power and led to the growth of administrative bureaucracies on top of the feudal land monopolies and restrictive guilds.

The economic causes of the French Revolution are sometimes insufficiently appreciated. In his book The French Revolution: An Economic Interpretation, Florin Aftalion outlines some of those causes. The French state engaged in wars throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. To pay for the wars, it employed complex and burdensome taxation, tax farming, borrowing, debt repudiation and forced “disgorgement” from the financiers, and debasement of the currency. Lord Acton wrote that people had been anticipating revolution in France for a century. And revolution came.

Liberals and libertarians admired the fundamental values it represented. Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek both hailed “the ideas of 1789” and contrasted them with “the ideas of 1914” — that is, liberty versus state-directed organization.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man, issued a month after the fall of the Bastille, enunciated libertarian principles similar to those of the Declaration of Independence:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights… .

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression… .

4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights… .

17. [P]roperty is an inviolable and sacred right.

But it also contained some dissonant notes, notably:

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation… .

6. Law is the expression of the general will.

A liberal interpretation of those clauses would stress that sovereignty is now rested in the people (like “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”), not in any individual, family, or class. But those phrases are also subject to illiberal interpretation and indeed can be traced to an illiberal provenance. The liberal Benjamin Constant blamed many of France’s ensuing problems on Jean-Jacques Rousseau, often very wrongly thought to be a liberal: “By transposing into our modern age an extent of social power, of collective sovereignty, which belonged to other centuries, this sublime genius, animated by the purest love of liberty, has nevertheless furnished deadly pretexts for more than one kind of tyranny.” That is, Rousseau and too many other Frenchmen thought that liberty consisted in being part of a self-governing community rather than the individual right to worship, trade, speak, and “come and go as we please.”

The results of that philosophical error—that the state is the embodiment of the “general will,” which is sovereign and thus unconstrained—have often been disastrous, and conservatives point to the Reign of Terror in 1793-94 as the precursor of similar terrors in totalitarian countries from the Soviet Union to Pol Pot’s Cambodia.

In Europe, the results of creating democratic but essentially unconstrained governments have been far different but still disappointing to liberals. As Hayek wrote in The Constitution of Liberty:

The decisive factor which made the efforts of the Revolution toward the enhancement of individual liberty so abortive was that it created the belief that, since at last all power had been placed in the hands of the people, all safeguards against the abuse of this power had become unnecessary.

Governments could become vast, expensive, debt-ridden, intrusive, and burdensome, even though they remained subject to periodic elections and largely respectful of civil and personal liberties. A century after the French Revolution, Herbert Spencer worried that the divine right of kings had been replaced by “the divine right of parliaments.”

Still, as Constant celebrated in 1816, in England, France, and the United States, liberty

is the right to be subjected only to the laws, and to be neither arrested, detained, put to death or maltreated in any way by the arbitrary will of one or more individuals. It is the right of everyone to express their opinion, choose a profession and practice it, to dispose of property, and even to abuse it; to come and go without permission, and without having to account for their motives or undertakings. It is everyone’s right to associate with other individuals, either to discuss their interests, or to profess the religion which they and their associates prefer, or even simply to occupy their days or hours in a way which is most compatible with their inclinations or whims.

Compared to the ancien regime of monarchy, aristocracy, class, monopoly, mercantilism, religious uniformity, and arbitrary power, that’s the triumph of liberalism.

Posted on July 14, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses heroes of freedom on FBN’s Stossel

Posted on July 10, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his book The Libertarian Mind on KCUR’s Up to Date

Posted on July 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses how to talk to progressive family members on an FBN Stossel web exclusive

Posted on July 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty