The Phonics Resurgence

Suddenly, and rather quietly, both public and elite opinion are turning against the “new” methods of teaching reading that have dominated our schools for a generation.

I’ve been keeping an eye on this issue for a long time. In 1995 I noticed that after state test results showed that the vast majority of California public school students could not read, write, or compute at levels considered proficient, Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin appointed two task forces to investigate reading and math instruction. The reports were clear — and depressing. There had been a wholesale abandonment of the basics — such as phonics and arithmetic drills — in California classrooms. Eastin said there was no one place to lay the blame for the decade‐long disaster. “What we made was an honest mistake,” she said. Or as the Sacramento Bee headline put it, “We Goofed.”

You’d think such a devastating report in the nation’s largest state would have had an impact. But it didn’t seem to get much attention outside California. Instead, schools kept adopting reading instruction plans based on “whole language” and “balanced literacy” theories. Despite the fact that in 1997 Congress instructed the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development to work with the Department of Education to establish a National Reading Panel that would evaluate existing research and evidence to find the best ways of teaching children to read. The panel reviewed more than 100,000 reading studies. In 2000 it reported its conclusion: That the best approach to reading instruction is one that incorporates:

- Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness

- Systematic phonics instruction

- Methods to improve fluency

- Ways to enhance comprehension

But suddenly, in May of last year the New York Times took note of the problems with school reading instruction with a page 1 article on how a leading advocate of “balanced literacy” was backtracking. At Columbia University’s Teachers College, she and her team trained thousands of teachers, and she estimated that her “Units of Study” was used in a quarter of the country’s 67,000 elementary schools.

The Times noted that a 2019 investigation by American Public Media revealed “American education’s own little secret about reading: Elementary schools across the country are teaching children to be poor readers — and educators may not even know it.”

Then in January of this year I noted that the Fairfax County and Arlington County NAACP chapters in Virginia were making demands on the local school system: they want the schools to teach black and Hispanic kids to read. And they want the school to start using the best research‐tested methods. After years of promising to make minority achievement a priority, finally in the past school year, the district gave all kindergarten through second‐grade teachers scripted lesson plans featuring phonics.

In March the Washington Post editorialized: “Cut the politics. Phonics is the best way to teach reading.”

In April the New York Times reported, “A revolt over how children are taught to read, steadily building for years, is now sweeping school board meetings and statehouses around the country.” They quoted Ohio Governor Mike Dewine: “The evidence is clear,” Mr. DeWine said. “The verdict is in.” And noted: “The movement has drawn support across economic, racial and political lines. Its champions include parents of children with dyslexia; civil rights activists with the N.A.A.C.P.; lawmakers from both sides of the aisle; and everyday teachers and principals.”

American Public Media has continued to follow the issue, and reported recently that at least 18 state legislatures are considering “ways to better align reading instruction with scientific research.”

NPR’s “All Things Considered” reported in June on the state of Georgia’s new push for phonics in the lower grades. NPR notes that “there’s perhaps no greater predictor of how a child will succeed in school than how well they can read by about the third grade. Research has shown that if students don’t learn by then, they’re far more likely to fall dangerously behind.”

This new approach is being called “the Science of Reading,” but it’s the science your grandmother knew: Learn the letters, learn how each letter sounds, learn how the letters combine into words. The amazing thing is that for a generation or more, professors and school administrators thought they had better ideas.

As I wrote before:

Phonics seems like a good idea to me, but I’m no expert. As noted, though, there’s a lot of research recommending phonics that a lot of school districts still aren’t following. As a libertarian, I don’t usually spend much time telling government agencies how to do their jobs, except as their actions impinge directly on individual rights. My focus is more on defining what activities ought to be undertaken by government and what ought to remain in the private sector, with individuals, businesses, churches, clubs, nonprofits, and civil society. And I think there’s a lesson here on that.

Government agencies tend to be sluggish monopolies, with little incentive to improve and subject to political influence. When the California superintendent promised to fix the mistake, the teachers union head warned, “It’s like turning an oil tanker around. You just don’t do that quickly,” and the governor’s spokesperson said it would be a hard slog because “there is such partisan politics going on.” Private organizations, especially profit‐seeking businesses, are under constant pressure to serve customers better than their competitors. Businesses fail to meet that test every day and go out of business. When’s the last time you heard of a failed government agency being shut down? That includes schools. Private schools must keep families happy or they can go elsewhere, and the school could be forced to shut down. Public schools, no matter how unhappy parents are, are almost never closed. As long as the tax money keeps coming in, they stay in business.

The problem is that the schools are run by a bureaucratic government monopoly, largely isolated from competitive or community pressures. We expect good service from businesses because we know–and we know that they know — that we can go somewhere else. We instinctively know we won’t get good service from the post office or the Division of Motor Vehicles because we can’t go anywhere else.

But now, after many years of complaints from parents, the elite media are joining the chorus: Teach children to read, using time‐tested methods, confirmed by the National Reading Panel in 2000. It’s about time.

Posted on June 14, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Soul of America

President Biden launched his reelection campaign by declaring, “We’re in a battle for the soul of America. The question we’re facing is whether in the years ahead, we have more freedom or less freedom. More rights or fewer.” Music to libertarian ears. But one might question whether either party today is offering Americans more freedom, or truly understands the soul of America. The Founders gave us a mission statement for the United States of America, an expression of its soul:

lead,We hold these truths to be self‐evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

That mission statement created a legacy. The Pulitzer Prize‐winning historian Bernard Bailyn elaborated on how early Americans made those ideas real:

,Written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, and courts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express the profound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of the American Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanent legacy ever after.

How are our leaders living up to those principles today? The idea of restricting power has too often been replaced by faith that a leader’s every passing thought should be turned into law, by legislation if possible, by executive order or administrative regulation if necessary. Worse, growing tribalism leads to an attitude that the point of gaining office is to use state power to reward “us” and to harm “them.”

President Biden correctly calls his predecessor’s attempt to overturn the election an assault on democracy and the Constitution. Too few Republican officials affirm that Biden won the election and that it was shockingly wrong to try to pressure election officials to “find” more votes. However, the president’s embrace of freedom seems to extend only to a few issues. He would raise taxes on both individuals and corporations, reducing our freedom to spend the money we earn; borrow and borrow (and borrow)—which crowds out private borrowing— and pile up debt, which is paid eventually with taxes or inflation. Government’s preferences are substituted for our own. Freedom to live as you want matters, too.

The costs of Biden’s regulations so far exceed those of Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama combined. Most of them restrict our freedom. Like his predecessor, Biden continues to impose costs on consumers through tariffs and other trade restrictions. His Federal Trade Commission seeks to break up America’s successful companies. Subsidies are handed to favored industries and firms. He would deny families the freedom to choose the best schools for their children.

Meanwhile, the two leading candidates for the Republican presidential nomination pound the table for freedom. Before his election loss, the former president’s great passions were to restrict international trade and immigration, and he threatened to send military troops into U.S. cities over the objections of local governments. Now he’s proposing military strikes in Mexico.

His chief Republican rival proclaims his support for free speech but has launched multiple legal assaults on the Walt Disney Co. after it issued a tepid criticism of a bill regulating what teachers could say about sexual orientation and gender identity. He barred Florida companies, including cruise ships, from setting their own vaccination policies. This is not your father’s idea of free enterprise. And all of this comes at a time when leading conservatives are writing things like “The right must be comfortable wielding the levers of state power,” and “using them to reward friends and punish enemies.”

Republican governors and legislatures are taking books out of schools—ranging from some that are actually problematic to biographies of Rosa Parks—and rushing to legislate restrictions on transgender people and “drag shows” without much careful consideration. It’s reminiscent of those who rushed in the early 2000s to ban same‐sex marriage. The current mania is partly in response to similarly rushed federal mandates regarding transgender policy on local governments.

In all this haste to legislate bans, mandates, taxes, regulations, subsidies, boondoggles, and punishments, who’s looking out for the soul of America?

Posted on June 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

What Does “Liberal” Mean, Anyway?

The United States is a liberal country in a liberal world. What does that mean? Let’s consider a little history.

leadFor thousands of years, most of recorded history, the world was characterized by power, privilege, and oppression. Life for most people was, in the phrase of Thomas Hobbes, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

And then something changed. In the 17th century, the Scientific Revolution emerged out of a new, more empirical way of doing science. And that led into the Enlightenment beginning late that century. In his book Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker identifies four themes of the Enlightenment: reason, science, humanism, and progress.

Liberalism arose in that environment. People began to question the role of the state and the established church. They argued for liberty for all based on the equal natural rights and dignity of every person. John Locke, often regarded as the father of liberalism, argued in his Second Treatise of Government that every person has a property in his own person and in “the work of his hands”; that government is formed to protect life, liberty, and property and is based on the consent of the governed; and that if government exceeds its proper role, the people are entitled to replace it.

As the economist and intellectual historian Daniel Klein has shown, in the 1770s writers began using such terms as “liberal policy,” “liberal plan,” “liberal system,” “liberal views,” “liberal ideas,” and “liberal principles.” Adam Smith was another founding figure of liberalism. In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, he wrote about “allowing every man to pursue his own interest his own way, upon the liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice.” The term “liberalism” came along about a generation later.

The year 1776, of course, also saw the publication of the most eloquent piece of liberal or libertarian writing ever, the American Declaration of Independence, which concisely laid out Locke’s analysis of the purpose and limits of government.

Liberalism was emerging in continental Europe, too, in the writings of Montesquieu and Constant in France, Wilhelm von Humboldt in Germany, and others. In the 1820s the representatives of the middle class in the Spanish Cortes, or parliament, came to be called the Liberales. They contended with the Serviles (the servile ones), who represented the nobles and the absolute monarchy. The term Serviles, for those who advocate state power over individuals, unfortunately didn’t stick. But the word “liberal,” for the defenders of liberty and the rule of law, spread rapidly. The Whig Party in England came to be called the Liberal Party. Today we know the philosophy of John Locke, Adam Smith, the American Founders, and John Stuart Mill as liberalism.

The Liberal 19th Century

In both the United States and Europe the century after the American Revolution was marked by the spread of liberalism. The ancient practices of slavery and serfdom were ended. Written constitutions and bills of rights protected liberty and guaranteed the rule of law. Guilds and monopolies were largely eliminated, with all trades thrown open to competition based on merit. Freedom of the press and of religion was greatly expanded, property rights were made more secure, and international trade was freed. After the defeat of Napoleon, Europe enjoyed a century of relative peace.

That liberation of human creativity unleashed astounding scientific and material progress. The Nation magazine, which was then a truly liberal journal, looking back in 1900, wrote, “Freed from the vexatious meddling of governments, men devoted themselves to their natural task, the bettering of their condition, with the wonderful results which surround us.” The technological advances of the liberal 19th century are innumerable: the steam engine, the railroad, the telegraph, the telephone, electricity, the internal combustion engine. Thanks to such innovations and an explosion of entrepreneurship, in Europe and America the great masses of people began to be liberated from the backbreaking toil that had been the natural condition of humankind since time immemorial. Infant mortality fell and life expectancy began to rise to unprecedented levels. A person looking back from 1800 would see a world that for most people had changed little in thousands of years; by 1900 the world was unrecognizable.

The Turn Away from Liberalism

Toward the end of the 19th century, classical liberalism began to give way to new forms of collectivism and state power. That Nation editorial went on to lament that “material comfort has blinded the eyes of the present generation to the cause which made it possible” and that “before [statism] is again repudiated there must be international struggles on a terrific scale.”

From the disastrous World War I on, governments grew in size, scope, and power. Exorbitant taxation, militarism, conscription, censorship, nationalization, and central planning signaled that the era of liberalism, which had so recently supplanted the old order, was now itself supplanted by the era of the megastate.

Through the Progressive Era, World War I, the New Deal, and World War II, there was tremendous enthusiasm for bigger government among American intellectuals. Herbert Croly, the first editor of the New Republic, wrote in The Promise of American Life that that promise would be fulfilled “not by … economic freedom, but by a certain measure of discipline; not by the abundant satisfaction of individual desires, but by a large measure of individual subordination and self‐denial.”

Around 1900 even the term “liberal” underwent a change. People who supported big government and wanted to limit and control the free market started calling themselves liberals. The economist Joseph Schumpeter noted, “As a supreme, if unintended, compliment, the enemies of private enterprise have thought it wise to appropriate its label.” Scholars began to refer to the philosophy of individual rights, free markets, and limited government—the philosophy of Locke, Smith, and Mill—as classical liberalism. Some liberals, including F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman, continued to call themselves liberals. But others came up with a new word, libertarian.

In much of the world even today the advocates of liberty are still called liberals. In South Africa the liberals, such as Helen Suzman, rejected the system of racism and economic privilege known as apartheid in favor of human rights, nonracial policies, and free markets. In China, Russia, and Iran, liberals are those who want to replace totalitarianism in all its aspects with the liberal system of free markets, free speech, and constitutional government. Even in Western Europe, the term liberal still indicates at least a fuzzy version of classical liberalism. German liberals, for instance, usually to be found in the Free Democratic Party, oppose the socialism of the Social Democrats, the corporatism of the Christian Democrats, and the paternalism of both.

For all the growth of government in the past century, liberalism remains the basic operating system of the United States, Europe, and an increasing part of the world. Those countries broadly respect such basic liberal principles as private property, markets, free trade, the rule of law, government by consent of the governed, constitutionalism, free speech, free press, religious freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, peace, and a generally free and open society—but not without plenty of arguments, of course, over the scope of government and the rights of individuals, from taxes and the welfare state to drug prohibition and war. But as Brian Doherty wrote in Radicals for Capitalism, his history of the libertarian movement, we live in a liberal world that “runs on approximately libertarian principles, with a general belief in property rights and the benefits of liberty.”

America’s Liberal Heritage

And that is certainly true in the United States. The great American historian Bernard Bailyn wrote:

,The major themes of eighteenth‐century [English] radical libertarianism [were] brought to realization here. The first is the belief that power is evil, a necessity perhaps but an evil necessity; that it is infinitely corrupting; and that it must be controlled, limited, restricted in every way compatible with a minimum of civil order. Written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, and courts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express the profound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of the American Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanent legacy ever after.

Through all our many political fights, especially after the abolition of slavery, American debate has taken place within a broad liberal consensus.

Modern American politics can be traced to the era of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, when “liberalism” came to mean activist government, theoretically to help the poor and the middle class—taxes, transfer programs, and regulation—plus a growing concern for civil rights and civil liberties. Race relations, which had taken a turn for the worse in the Progressive Era, with Woodrow Wilson’s resegregation of the federal workforce, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, and the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, began to improve after World War II with the desegregation of the armed forces and federal employment and subsequent moves to undo legal segregation. A new opposition arose, a conservative movement led by William F. Buckley Jr., Sen. Barry Goldwater, and President Ronald Reagan. That conservative movement preached a gospel of free markets, a strong national defense, and “traditional values,” which often meant opposition to civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights.

And those were the opposing factions in American politics from the 1960s to 2015. But Donald Trump changed that picture. He didn’t really campaign on free markets, traditional values, and a strong national defense. He emphasized his opposition to free trade and immigration, was largely indifferent to abortion and gay rights, and engaged in open racial and religious scapegoating. That was a big shift from the Republican party shaped by Ronald Reagan, but Trump remade the GOP in his image.

Now we have Democrats moving left in all the wrong ways—far more spending than even the Obama administration, openly socialist officials, and aggressive efforts to restrict free speech in the name of fighting “hate speech.” Meanwhile, Republicans are moving to the wrong kind of right—a culture war pitting Americans against Americans and a new willingness to use state power to hurt their opponents, including private businesses.

The Liberal or Libertarian Center

Where does that leave libertarians? Well, right where we’ve always been: advocating the philosophy of freedom—economic freedom, personal freedom, human rights, political freedom. Or as the Cato Institute maxim puts it, individual rights, free markets, limited government, and peace.

But if liberals and Democrats become more hostile to capitalism and abandon free speech, and Republicans double down on aggressive cultural conservatism and protectionism, maybe there’s room for a new political grouping, which we might call the liberal or libertarian center.

Pundits talk a lot about “fiscally conservative and socially liberal” swing voters, and a Zogby poll commissioned by Cato once found that 59 percent of Americans agreed that they would describe themselves that way. Most Americans are content with both the cultural liberations of the 1960s and the economic liberations begun in the 1980s.

That broadly libertarian center is politically homeless today. If we approach politics and policy reasonably, libertarians can provide a nucleus for that broad center of peaceful and productive people in a society of liberty under law.

The Libertarian Challenge

As bleak as things sometimes seem in the United States, there are definitely worse problems in the world. In too much of the world, ideas we thought were dead are back: socialism and protectionism and ethnic nationalism, even “national socialism,” authoritarianism on both the left and the right. We see this in Russia and China, of course, but not only there; also in Turkey, Egypt, Hungary, Venezuela, Mexico, the Philippines, maybe India. A far‐right candidate—anti-immigration, anti‐globalization, anti–free trade, anti‐privatization, anti–pension reform—came too close for comfort to the presidency of France.

As Tom G. Palmer wrote in the November/December 2016 issue of Cato Policy Report, we can identify three competing threats to liberty: identity politics and the intolerant left; populism and the yearning for strongman rule that invariably accompanies it; and radical political Islamism, which has less political appeal in the West.

People who oppose these ideas need to develop a defense of liberty, equality, and democracy. Libertarians are well suited to do that.

In 1997, Fareed Zakaria wrote:

,Consider what classical liberalism stood for in the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was against the power of the church and for the power of the market; against the privileges of kings and aristocracies and for dignity of the middle class; against a society dominated by status and land and in favor of one based on markets and merit; opposed to religion and custom and in favor of science and secularism; for national self‐determination and against empires; for freedom of speech and against censorship; for free trade and against mercantilism. Above all, it was for the rights of the individual and against the power of the church and the state.

And, he said, it won a sweeping victory against “an order that had dominated human society for two millennia—that of authority, religion, custom, land, and kings.”

Libertarians are tempted to be too depressed. We read the morning papers, or watch the cable shows, and we think the world is indeed on “the road to serfdom.” But we should reject a counsel of despair. We’ve been fighting ignorance, superstition, privilege, and power for many centuries. We and our classical liberal forebears have won great victories. The fight is not over, but liberalism remains the only workable operating system for a world of peace, growth, and progress.

Posted on June 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

What Does “Liberal” Mean, Anyway?

The United States is a liberal country in a liberal world. What does that mean? Let’s consider a little history.

leadFor thousands of years, most of recorded history, the world was characterized by power, privilege, and oppression. Life for most people was, in the phrase of Thomas Hobbes, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

And then something changed. In the 17th century, the Scientific Revolution emerged out of a new, more empirical way of doing science. And that led into the Enlightenment beginning late that century. In his book Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker identifies four themes of the Enlightenment: reason, science, humanism, and progress.

Liberalism arose in that environment. People began to question the role of the state and the established church. They argued for liberty for all based on the equal natural rights and dignity of every person. John Locke, often regarded as the father of liberalism, argued in his Second Treatise of Government that every person has a property in his own person and in “the work of his hands”; that government is formed to protect life, liberty, and property and is based on the consent of the governed; and that if government exceeds its proper role, the people are entitled to replace it.

As the economist and intellectual historian Daniel Klein has shown, in the 1770s writers began using such terms as “liberal policy,” “liberal plan,” “liberal system,” “liberal views,” “liberal ideas,” and “liberal principles.” Adam Smith was another founding figure of liberalism. In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, he wrote about “allowing every man to pursue his own interest his own way, upon the liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice.” The term “liberalism” came along about a generation later.

The year 1776, of course, also saw the publication of the most eloquent piece of liberal or libertarian writing ever, the American Declaration of Independence, which concisely laid out Locke’s analysis of the purpose and limits of government.

Liberalism was emerging in continental Europe, too, in the writings of Montesquieu and Constant in France, Wilhelm von Humboldt in Germany, and others. In the 1820s the representatives of the middle class in the Spanish Cortes, or parliament, came to be called the Liberales. They contended with the Serviles (the servile ones), who represented the nobles and the absolute monarchy. The term Serviles, for those who advocate state power over individuals, unfortunately didn’t stick. But the word “liberal,” for the defenders of liberty and the rule of law, spread rapidly. The Whig Party in England came to be called the Liberal Party. Today we know the philosophy of John Locke, Adam Smith, the American Founders, and John Stuart Mill as liberalism.

The Liberal 19th Century

In both the United States and Europe the century after the American Revolution was marked by the spread of liberalism. The ancient practices of slavery and serfdom were ended. Written constitutions and bills of rights protected liberty and guaranteed the rule of law. Guilds and monopolies were largely eliminated, with all trades thrown open to competition based on merit. Freedom of the press and of religion was greatly expanded, property rights were made more secure, and international trade was freed. After the defeat of Napoleon, Europe enjoyed a century of relative peace.

That liberation of human creativity unleashed astounding scientific and material progress. The Nation magazine, which was then a truly liberal journal, looking back in 1900, wrote, “Freed from the vexatious meddling of governments, men devoted themselves to their natural task, the bettering of their condition, with the wonderful results which surround us.” The technological advances of the liberal 19th century are innumerable: the steam engine, the railroad, the telegraph, the telephone, electricity, the internal combustion engine. Thanks to such innovations and an explosion of entrepreneurship, in Europe and America the great masses of people began to be liberated from the backbreaking toil that had been the natural condition of humankind since time immemorial. Infant mortality fell and life expectancy began to rise to unprecedented levels. A person looking back from 1800 would see a world that for most people had changed little in thousands of years; by 1900 the world was unrecognizable.

The Turn Away from Liberalism

Toward the end of the 19th century, classical liberalism began to give way to new forms of collectivism and state power. That Nation editorial went on to lament that “material comfort has blinded the eyes of the present generation to the cause which made it possible” and that “before [statism] is again repudiated there must be international struggles on a terrific scale.”

From the disastrous World War I on, governments grew in size, scope, and power. Exorbitant taxation, militarism, conscription, censorship, nationalization, and central planning signaled that the era of liberalism, which had so recently supplanted the old order, was now itself supplanted by the era of the megastate.

Through the Progressive Era, World War I, the New Deal, and World War II, there was tremendous enthusiasm for bigger government among American intellectuals. Herbert Croly, the first editor of the New Republic, wrote in The Promise of American Life that that promise would be fulfilled “not by … economic freedom, but by a certain measure of discipline; not by the abundant satisfaction of individual desires, but by a large measure of individual subordination and self‐denial.”

Around 1900 even the term “liberal” underwent a change. People who supported big government and wanted to limit and control the free market started calling themselves liberals. The economist Joseph Schumpeter noted, “As a supreme, if unintended, compliment, the enemies of private enterprise have thought it wise to appropriate its label.” Scholars began to refer to the philosophy of individual rights, free markets, and limited government—the philosophy of Locke, Smith, and Mill—as classical liberalism. Some liberals, including F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman, continued to call themselves liberals. But others came up with a new word, libertarian.

In much of the world even today the advocates of liberty are still called liberals. In South Africa the liberals, such as Helen Suzman, rejected the system of racism and economic privilege known as apartheid in favor of human rights, nonracial policies, and free markets. In China, Russia, and Iran, liberals are those who want to replace totalitarianism in all its aspects with the liberal system of free markets, free speech, and constitutional government. Even in Western Europe, the term liberal still indicates at least a fuzzy version of classical liberalism. German liberals, for instance, usually to be found in the Free Democratic Party, oppose the socialism of the Social Democrats, the corporatism of the Christian Democrats, and the paternalism of both.

For all the growth of government in the past century, liberalism remains the basic operating system of the United States, Europe, and an increasing part of the world. Those countries broadly respect such basic liberal principles as private property, markets, free trade, the rule of law, government by consent of the governed, constitutionalism, free speech, free press, religious freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, peace, and a generally free and open society—but not without plenty of arguments, of course, over the scope of government and the rights of individuals, from taxes and the welfare state to drug prohibition and war. But as Brian Doherty wrote in Radicals for Capitalism, his history of the libertarian movement, we live in a liberal world that “runs on approximately libertarian principles, with a general belief in property rights and the benefits of liberty.”

America’s Liberal Heritage

And that is certainly true in the United States. The great American historian Bernard Bailyn wrote:

,The major themes of eighteenth‐century [English] radical libertarianism [were] brought to realization here. The first is the belief that power is evil, a necessity perhaps but an evil necessity; that it is infinitely corrupting; and that it must be controlled, limited, restricted in every way compatible with a minimum of civil order. Written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, and courts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express the profound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of the American Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanent legacy ever after.

Through all our many political fights, especially after the abolition of slavery, American debate has taken place within a broad liberal consensus.

Modern American politics can be traced to the era of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, when “liberalism” came to mean activist government, theoretically to help the poor and the middle class—taxes, transfer programs, and regulation—plus a growing concern for civil rights and civil liberties. Race relations, which had taken a turn for the worse in the Progressive Era, with Woodrow Wilson’s resegregation of the federal workforce, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, and the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, began to improve after World War II with the desegregation of the armed forces and federal employment and subsequent moves to undo legal segregation. A new opposition arose, a conservative movement led by William F. Buckley Jr., Sen. Barry Goldwater, and President Ronald Reagan. That conservative movement preached a gospel of free markets, a strong national defense, and “traditional values,” which often meant opposition to civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights.

And those were the opposing factions in American politics from the 1960s to 2015. But Donald Trump changed that picture. He didn’t really campaign on free markets, traditional values, and a strong national defense. He emphasized his opposition to free trade and immigration, was largely indifferent to abortion and gay rights, and engaged in open racial and religious scapegoating. That was a big shift from the Republican party shaped by Ronald Reagan, but Trump remade the GOP in his image.

Now we have Democrats moving left in all the wrong ways—far more spending than even the Obama administration, openly socialist officials, and aggressive efforts to restrict free speech in the name of fighting “hate speech.” Meanwhile, Republicans are moving to the wrong kind of right—a culture war pitting Americans against Americans and a new willingness to use state power to hurt their opponents, including private businesses.

The Liberal or Libertarian Center

Where does that leave libertarians? Well, right where we’ve always been: advocating the philosophy of freedom—economic freedom, personal freedom, human rights, political freedom. Or as the Cato Institute maxim puts it, individual rights, free markets, limited government, and peace.

But if liberals and Democrats become more hostile to capitalism and abandon free speech, and Republicans double down on aggressive cultural conservatism and protectionism, maybe there’s room for a new political grouping, which we might call the liberal or libertarian center.

Pundits talk a lot about “fiscally conservative and socially liberal” swing voters, and a Zogby poll commissioned by Cato once found that 59 percent of Americans agreed that they would describe themselves that way. Most Americans are content with both the cultural liberations of the 1960s and the economic liberations begun in the 1980s.

That broadly libertarian center is politically homeless today. If we approach politics and policy reasonably, libertarians can provide a nucleus for that broad center of peaceful and productive people in a society of liberty under law.

The Libertarian Challenge

As bleak as things sometimes seem in the United States, there are definitely worse problems in the world. In too much of the world, ideas we thought were dead are back: socialism and protectionism and ethnic nationalism, even “national socialism,” authoritarianism on both the left and the right. We see this in Russia and China, of course, but not only there; also in Turkey, Egypt, Hungary, Venezuela, Mexico, the Philippines, maybe India. A far‐right candidate—anti-immigration, anti‐globalization, anti–free trade, anti‐privatization, anti–pension reform—came too close for comfort to the presidency of France.

As Tom G. Palmer wrote in the November/December 2016 issue of Cato Policy Report, we can identify three competing threats to liberty: identity politics and the intolerant left; populism and the yearning for strongman rule that invariably accompanies it; and radical political Islamism, which has less political appeal in the West.

People who oppose these ideas need to develop a defense of liberty, equality, and democracy. Libertarians are well suited to do that.

In 1997, Fareed Zakaria wrote:

,Consider what classical liberalism stood for in the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was against the power of the church and for the power of the market; against the privileges of kings and aristocracies and for dignity of the middle class; against a society dominated by status and land and in favor of one based on markets and merit; opposed to religion and custom and in favor of science and secularism; for national self‐determination and against empires; for freedom of speech and against censorship; for free trade and against mercantilism. Above all, it was for the rights of the individual and against the power of the church and the state.

And, he said, it won a sweeping victory against “an order that had dominated human society for two millennia—that of authority, religion, custom, land, and kings.”

Libertarians are tempted to be too depressed. We read the morning papers, or watch the cable shows, and we think the world is indeed on “the road to serfdom.” But we should reject a counsel of despair. We’ve been fighting ignorance, superstition, privilege, and power for many centuries. We and our classical liberal forebears have won great victories. The fight is not over, but liberalism remains the only workable operating system for a world of peace, growth, and progress.

Posted on June 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Continuing Effort to Deny that Libertarian‐ish Voters Exist

Here we go again. David Leonhardt of the New York Times dredges up a poorly designed chart from 2017 that purported to show that there are very few “fiscally conservative, socially liberal” American voters. At the time Karl Smith pointed out some basic design flaws in the analysis. Emily Ekins noted that determining the number of liberal, conservative, libertarian, and populist/communitarian/statist voters depends very much on the definitions you start with and the issues you choose. She concludes: “The overwhelming body of literature, however, using a variety of different methods and different definitions, suggests that libertarians comprise about 10–20% of the population, but may range from 7–22%.”

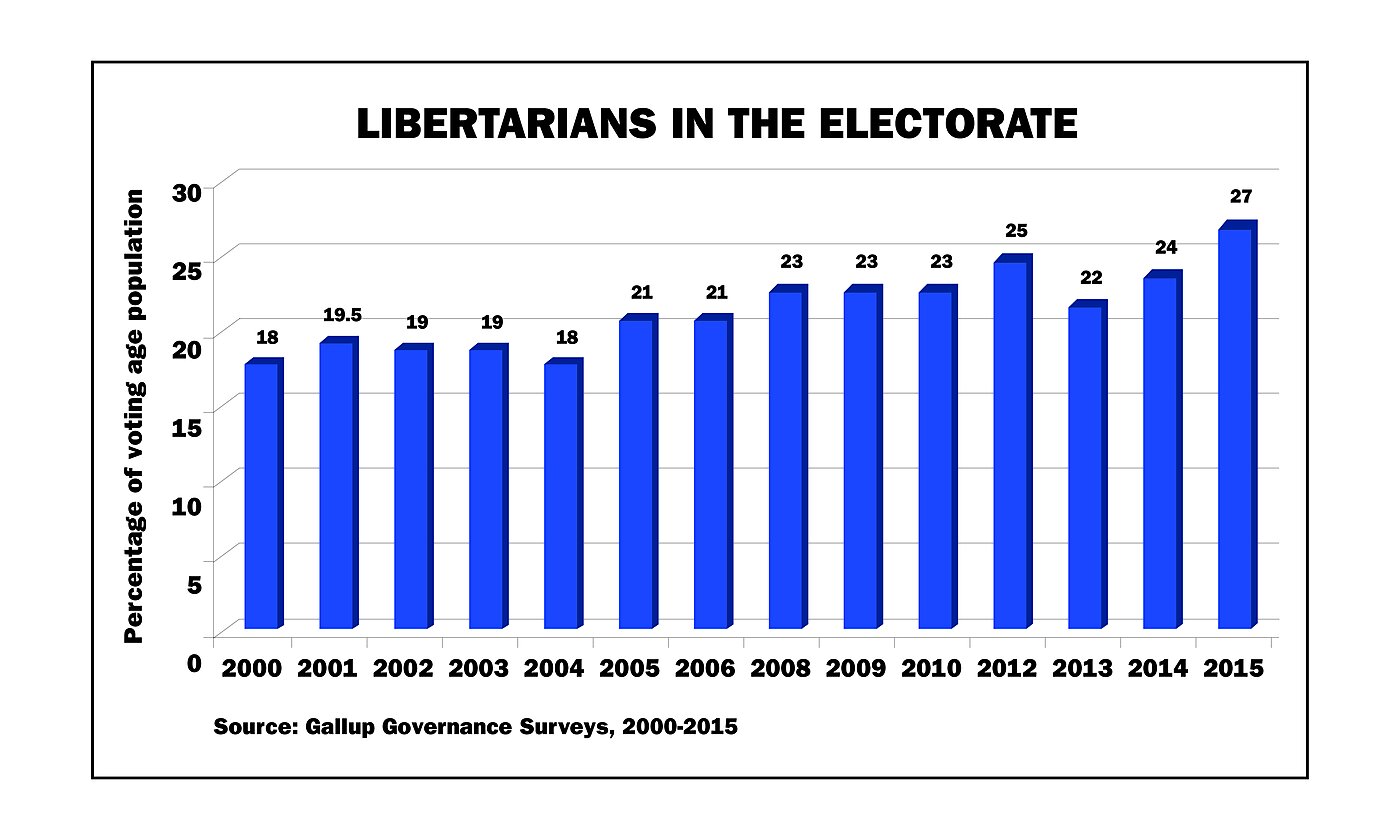

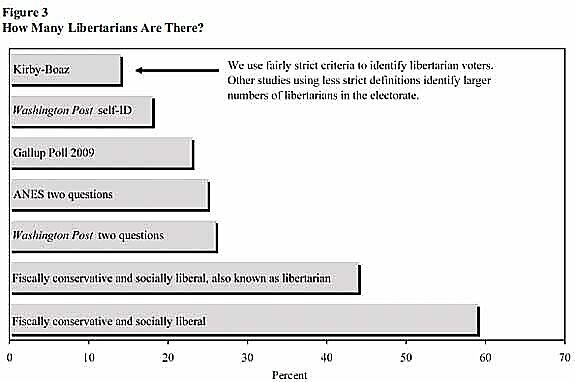

The Gallup Poll has regularly used a two‐question screen to divide voters into four ideological categories, and they typically found libertarians around the 20 percent mark.

Beginning in 2006 David Kirby and I used a three‐question screen to identify libertarians, and we found that with that stricter definition “libertarians” constituted about 13 percent of the population and 15 percent of reported voters. And note that if we insisted on agreement with the liberal or conservative position on all three questions, the number of liberals and conservatives would likely be quite a bit lower than 25 percent.

It’s quite possible, of course, that the Trump Effect on Republican voters, not to mention the anti‐Trump backlash among independent and Democratic voters would have significantly changed some of these pre‐Trump, “normal” findings.

We also commissioned Zogby International to ask our three American National Election Studies questions to 1,012 actual (reported) voters in the 2006 election. We asked half the sample, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal?” — the very categorization Leonhardt used in his column. We asked the other half of the respondents, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal, also known as libertarian?”

The results surprised us. Fully 59 percent of the respondents said “yes” to the first question. That is, by 59 to 27 percent, poll respondents said they would describe themselves as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.”

The addition of the word “libertarian” clearly made the question more challenging. What surprised us was how small the drop‐off was. A healthy 44 percent of respondents answered “yes” to that question, accepting a self‐description as “libertarian.” We summed all that up in this handy graph:

Leonhardt and others may well be right that there are more “socially conservative, fiscally liberal” voters than “fiscally conservative, socially liberal.” Though the latter are better educated, more affluent, and more likely to vote. And in any case the numbers are a lot closer than Leonhardt and his befuddled chart would have you believe. Also, much depends on the questions you ask. Kirby and I used broad philosophical questions, as did Gallup, Pew, and ANES. But you can also use specific issues, as did a Washington Post poll. The combination “abolish Medicare” and “repeal all drug laws” would find a huge percentage of SCFL voters and very few FCSL or libertarianish voters. “Gay people should be able to get married” plus “the government spends too much money” will get you a lot of FCSL voters. Which one is closer to actual American policy conflicts?

There’s plenty of room for debate about how to analyze the ideological positions of American voters. But looking at the available data is a good place to start.

Posted on May 30, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Jimmy Lai — Recipient of the 2023 Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty

Jimmy Lai has become a powerful symbol of the struggle for democratic rights and press freedom in Hong Kong as China’s Communist Party exerts ever greater control over the territory. In prison and denied bail, Lai is an outspoken critic of the Chinese government and advocate for democracy who faces charges that could keep him in jail for the rest of his life.

Posted on May 19, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Democracies, Autocracies, and Same‐Sex Unions

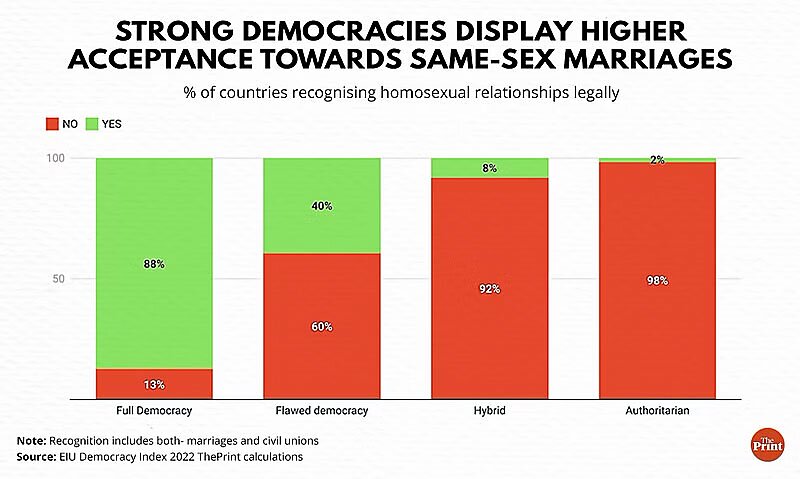

A new study by the Indian newspaper The Print, based on data from The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2022, finds that 88 percent of full democracies recognize same‐sex marriages or civil unions, while only 2 percent of authoritarian regimes do.

As my colleague Swaminathan Aiyar told the paper, “Autocracies do not recognise individual rights as fundamental and inalienable. Autocracies are organised on principles that allow the autocrat to discriminate on any grounds. In such countries, the progress of same‐sex rights will naturally be slower or non‐existent.” By contrast, implementation of same‐sex marriage in democratic countries proceeded very rapidly once it became a matter for debate. In 1989 Denmark became the first country in the world to legally recognize same‐sex unions, in the form of “registered partnerships.” In 2001 the first same‐sex marriage law came into effect, in the Netherlands.

In a sense this finding isn’t very surprising, of course: Liberal countries tend to be liberal. I’ve written about this before, citing a column written in 2013 by the British journalist Michael Hanlon. Hanlon wrote about a “morality gap” in the world that could be seen most clearly in attitudes toward gay rights. His column is worth quoting at length:

It is now clear, though not much talked about, that humanity, all 7.1 billion of us, tends to fall into one of two distinct camps. On the one side are those who buy into the whole post‐Enlightenment human rights revolution. For them the moral trajectory of the last 300 years is clear: once we were brutal savages; in a few decades, the whole planet will basically be Denmark, ruled by the shades of Mandela and Shami Chakrabarti.

And there’s some truth in this trajectory — except for the fact that it only applies to half the planet. The other half resolutely follows a different moral code: might is right, all men were not created equal and there is a right and a wrong form of sexual orientation.…

Let’s start with attitudes to gays, not because gay rights are the most important issue, but because attitudes to homosexuality show the morality gap in sharpest relief.…

A look at the timeline of gay rights shows a seemingly unstoppable barrage of permissiveness, with state after state passing laws first legalising homosexuality, then going further: permitting gay marriage and gay adoption and formalising gay relationships in terms of pensions and property rights. It’s tempting for those of us in this enlightened half of the world to think of this as a great wave of progress that rose up in the mid‐20th century and will sweep across the world.

Tempting, but wrong. In fact, in much of the world, received wisdom on homosexuality appears to be going into reverse.

Of course, this divide in the world is well known. It’s been discussed and analyzed in Pew Research studies, examined at HumanProgress.org, and included in the rankings of the Human Freedom Index. The findings from The Print show the divide in stark relief.

Liberalism is the most successful idea in the history of the world, yet it is now under attack in many parts of the world. Not just in countries such as Russia, China, Uganda, and India, but in liberal and democratic countries as well. Ideas we thought were dead are back. Socialism, protectionism, ethnic nationalism, antisemitism, even — for God’s sake — industrial policy. Liberals must sharpen their arguments and redouble their advocacy efforts on behalf of individual rights, free markets, limited government, and peace. Or as I like to say, we must continue to extend the promises of the Declaration of Independence — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — to places, and people, and aspects of life they have not yet reached.

Posted on May 3, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Lobbying Turns Green

I don’t mean to keep writing the same article about lobbying and special interests over and over. But the federal government keeps creating more and more opportunities for special interests to hire lobbyists. This week The Economist writes,

with up to $800bn in clean‐energy handouts now up for grabs over the coming decade, …

The energy industry as a whole spent nearly $300m last year on lobbying, the most since 2013 (see chart 1). Big oil and electric utilities, which had been reducing their spending on influence‐seeking before 2020, have ramped it up again; spending is growing in line with that of the biggest lobbyists, big pharma. Renewables firms went from spending an annual average of around $24m between 2013 and 2020, to $38m in 2021 and $47m in 2022. “We’ve now got an interesting new ecosystem of swamp creatures here,” says the government‐relations man at a giant renewable‐energy company.

And what caused this new ecosystem?

The reason is the passage last year of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The law funnels at least $369bn in direct subsidies and tax credits to decarbonisation‐related sectors (see chart 2). It came on the heels of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which also shovels billions in subsidies towards clean infrastructure. Some of the provisions offer generous tax credits, with no caps on the amount of spending eligible for the incentives. A mad investment rush, should it materialise, could lead to public expenditure of $800bn over the next decade. An official at a big utility says her firm has projects in the works across America that, if successful, will secure a staggering $2bn in funding from the two laws. “We stopped counting…we just have a big smile on our faces all the time these days,” confesses the renewables firm’s government‐relations man. “There is a lot there for a lot of people,” sums up a business‐chamber grandee. And, he adds, “A lot of lobbyists are interested in the spending.”

And as my colleague Scott Lincicome told Politico about another multi‐billion‐dollar pot of gold, the CHIPS and Science Act, “It would almost be corporate malpractice to not go after that cash.”

This is of course the standard story whenever Congress appropriates, or considers appropriating, a new pot of taxpayers’ money. The civics books explain that the people bring a problem to Congress, committees hold hearings and hear from expert witnesses, the issue is debated, Congress then maybe appropriates the money, and selfless experts in the bureaucracy spend it in the national interest. The reality is more like a feeding frenzy to get a piece of every new funding opportunity. It’s no surprise that that lobbying expenditures are reaching new highs in the spendthrift Biden administration.

Lobbying is protected by the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law … prohibiting … the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” But those who worry that corporate interests and the wealthy have too much influence in Washington should recognize the “supply‐side economics” of the problem: When government supplies billions — tens of billions — hundreds of billions of dollars to be handed out by appointed officials and the bureaucracy, you can bet that interested parties will leave no stone unturned in their effort to get a piece of that cash.

As Craig Holman of the Ralph Nader‐founded Public Citizen told Marketplace Radio during the 2009 financial crisis, “the amount spent on lobbying … is related entirely to how much the federal government intervenes in the private economy.”

Marketplace’s Ronni Radbill elaborated: “In other words, the more active the government, the more the private sector will spend to have its say…. With the White House injecting billions of dollars into the economy [in early 2009], lobbyists say interest groups are paying a lot more attention to Washington than they have in a very long time.”

Big government means big lobbying. When you lay out a picnic, you get ants. And today’s federal budget is the biggest picnic in history.

The Nobel laureate F. A. Hayek explained the process 80 years ago in his prophetic book The Road to Serfdom: “As the coercive power of the state will alone decide who is to have what, the only power worth having will be a share in the exercise of this directing power.”

That’s the worst aspect of the growth of lobbying: it indicates that decisions in the marketplace are being crowded out by decisions made by lobbyists and politicians, which means a more powerful government, less freedom, and less economic growth.

Posted on April 19, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cato Institute event, “Bruce Caldwell, Hayek; A Life,” aires on C‑SPAN 2

Posted on April 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Did Marx Make Lenin, or Did Lenin Make Marx?

Was Karl Marx one of the towering intellectual figures of the 19th century? It certainly seems that way. His work is widely assigned in college courses, far more than for instance John Locke and Adam Smith, much less F. A. Hayek or Ludwig von Mises.

But recently Phil Magness and Michael Makovi have advanced a different hypothesis: That Marx was a relatively minor figure in his own time, especially after the Marginal Revolution of the 1870s decisively refuted his economic analysis, and his reputation soared only after the Bolshevik Revolution — or the coup led by Vladimir Lenin — of 1917. See their academic paper here and a popular article here.

Recently I was looking at ideological bias in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, and I noticed that the book included 23 quotations from Marx. That’s the same as the combined total for John Locke and Adam Smith, the philosophical architects of our modern liberal world. (And far more than Hayek, Mises, Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand, or William F. Buckley Jr.)

But I wondered: how far back did Marx get such play in Bartlett’s, which has been published in 19 editions since 1855? What I found seems to add support to the thesis of Magness and Makovi. Marx (with Friedrich Engels) had 18 citations in the 1992 edition. That is, in Bartlett’s his relevance seems only to have risen since the collapse of the Soviet Union. But looking at previous editions, I see that Marx is not mentioned in the 1874 edition, published well after The Communist Manifesto, which so many college students are instructed to read. Nor in the 9th edition, after his death; this copy was published in 1905 but may have been edited by 1891. Not included in the 1919 (10th) edition, though his contemporary Herbert Spencer is well represented. Marx’s big break comes in the 11th edition, published in 1937 (though this copy was printed in 1942). In that edition Marx is represented with 17 quotations. (The 11th edition was edited by the journalist and novelist Christopher Morley, brother of the classical liberal journalist Felix Morley). There is no entry for either Locke or Smith. In the 1955 centennial edition, available through the Internet Archive, Marx again has 17 quotations. At last Locke and Smith get on the board, with 8 and 2 quotations respectively.

So what we know is this: Karl Marx begins publishing in the 1840s. He publishes his magnum opus, Capital, in 1867. He dies in 1883, but Engels keeps promoting and publishing his work. Through 1919 Marx goes unmentioned in the leading English‐language book of quotations. In the 1920s the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, using the vast resources of the Soviet state, embarks on a massive printing and distribution of Marx’s works in many languages. As the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm writes, “The cheap edition [of the Communist Manifesto] published in 1932 by the official publishing houses of the American and British Communist Parties in ‘hundreds of thousands’ of copies has been described as ‘probably the largest mass edition ever issued in English.’ ” And by 1937 Marx is well represented in Bartlett’s, while the most important theorists of Western liberalism are omitted. The efforts of Lenin and the Communist Party seem to have been the key factor in propelling Marx to the wide recognition we now take for granted.

Posted on March 28, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty